View the Post on the Blog

View the Post on the Blogby Joel (Snowathlete)

For millennia man has predicted the end of the world: an asteroid strike, a super-volcano, global warming... but in recent years, we’ve been told that our greatest threat is the microbe. In 2003 it was Bird flu, then in 2009 it was Swine flu, but as we’re still here, perhaps it’s a cock-and-bull story, rather than a bird and pig one?

Either way, we’ve got bigger fish to fry regarding our own disease, but all this talk of animals may not be far from the truth when it comes to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS).

Zoonoses (Greek: "zoon" = animal, "nosos" = disease) are diseases that are transmitted to humans from other animals, and such diseases are caused by a variety of pathogen types including parasites, bacteria, fungi, and viruses. Such pathogens transmitted to humans from animals are called zoonotics.

Animals are well known for transmitting diseases to humans: H5N1 (birds), H1N1 (swine), Toxoplamosis (cats), Lyme disease (tics), Rabies (dogs), etc. Rabies alone kills more than 50,000 people a year.

How common?

A study from the Royal Society, looking at 1415 pathogens known to infect humans, reported that 61% were zoonotic [1]. Therefore it is more likely than not that our illness - if it is caused by a pathogen - is zoonotic in origin. Additionally, it is thought that many anthroponoses (diseases transmissible between humans) started out as zoonotics, including measles and AIDS (the latter killing more than 25 million people in the last thirty years).

The current position on zoonotic diseases from the Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is that “approximately 75% of recently emerging infectious diseases affecting humans are diseases of animal origin.”

The threat

Picture courtesy of kat m research

Zoonotics have been responsible for a great deal of damage to human civilization over the years. Yersinia pestis, a gram-negative bacterium transmitted by fleas, is responsible for the Bubonic, Pneumonic and Septicemic plagues. In the fourteenth century this zoonotic was the cause of the Black Death - one of the most deadly pandemics in history - killing between 30 and 50 percent of the population of Europe, and it continued terrorizing Europe for hundreds of years.

In the modern era there is a great threat of a global pandemic of zoonotic origin, but predicting the emergence of such a disease has proven difficult. Our monitoring of emerging zoonotics has improved, but our best method so far is to contain such emerging zoonotics swiftly, erradicating them if possible, before the pathogens evolve to become communicable between humans.

A good example is New Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (nvCJD), the human form of Bovine Spongiform Encephalopathy (BSE). nvCJD is a zoonose that emerged in the 1990s following the outbreak of BSE in British cattle in the late 1980s.

Measures taken to avoid further infection of humans, such as the slaughter of more than four million cattle and the restriction and banning of certain beef products, meant that only around two hundred people are thought to have died from nvCJD to date, and only three cases of human to human transmission have been reported (all as a result of infected blood transfusion).

Transmission

Zoonotics can be transmitted via infected water or food, via a contaminated environment or indirectly via a vector. A vector is an animal that carries and transmits the zoonotic pathogen to a human. In the case of Lyme disease, for example, the vector is usually a tick, and has itself picked up the zoonotic parasite Borrelia from a reservoir. A reservoir is the animal that hosts the disease in the first place; in the case of Lyme disease this is often a rodent or bird. Although Lyme disease is understood to sometimes cause a bull’s eye type rash, it often doesn’t (more bull, I'm afraid).

Those who work or live with animals are at a greater risk of catching zoonoses, but although getting rid of the cat might reduce your chances of catching toxoplasmosis, pets have long been associated with health benefits and a study looking at CFS patients that had cats or dogs as pets showed no increased prevalence [2]. Avoiding smaller animals, such as insects, is particularly difficult and the chances are that you wouldn’t even notice being bitten.

Then there are animal viruses accidentally put into vaccines, such as the rotavirus gastroenteritis vaccines which were found to be contaminated with DNA belonging to Circovirus 1 (PCV1) and Circovirus 2 (PCV2) [3]. PCV2 can cause a wasting disease in pigs but is not thought to cause disease in humans. That means that it isn’t yet classified as a zoonotic, but whether it could emerge as a future zoonotic is a matter of continuing debate.

Zoonotics and ME/CFS

Some zoonotics are routinely found in humans – perhaps more so in ME/CFS patients - but the medical community has a tendency to dismiss such infections as many are thought not to cause disease, or to cause only mild, short-lived symptoms. Only pathogens that have already been proven to be particularly dangerous, like certain strains of E.coli, or Crimean-Congo Viral Hemorrhagic Fever (a tick-borne virus that occurs mainly in Africa and Asia) are treated more seriously when presented, as without treatment they can be fatal.

While some other zoonotics have been well researched and do not cause disease, or are mild and self-limiting, many others have not been well studied so could be significant factors in diseases like ME/CFS. Nevertheless, the general rule seems to be "safe until proven to cause harm". This leaves a lot of room for a known or unknown zoonotic to be the cause or the trigger of ME/CFS.

Even if such zoonotics are not the cause of ME/CFS, the immune-dysfunction associated with the illness may leave patients more vulnerable to such pathogens as secondary infections. Such infections are taken very seriously in illnesses, like HIV-AIDS, but the world has a lot of catching up to do before it recognises this threat in the case of ME/CFS.

Studies looking at zoonotics in ME/CFS

Staphylococci adhering to the surface of red blood cells of an CFS/ME patient from the UK (microphotograph copyright, W. Tarello).

In 2001 Dr. Walter Tarello, a veterinary surgeon from Perugia, Italy, reported the possible existence of CFS in horses infected with micrococci-like organisms, hinting at a zoonotic cause for the illness in humans. The horses were treated with Sodium Thiacetrarsamide, an arsenic based antibacterial, resulting in eradication of the bacteria and complete symptom remission [4]. Similar findings were later found in dogs, cats [5] and birds [6, 7].

The veterinary surgeon and his wife, themselves CFS suffers, then treated themselves with the same drug and made complete recoveries [8]. Indeed Dr Tarello's recovery has lasted, as shown by his ability to compete in the Dubai Marathon earlier this year, finishing in a very respectable time. Many CFS sufferers can hardly dream of making such a strong recovery, which highlights the need for more research into such treatments.

Image copyright, W. Tarello.

As well as raising the interesting question of whether other ME/CFS sufferers, besides Dr Tarello and his wife, might be infected by the same or similar micrococci-like organisms, what is clearly illustrated is that animal pathogens can be transmitted to humans and cause the same symptoms as ME/CFS. Zoonotics are common, easy to pick up, and are the cause of many different diseases in humans.

If we look at Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which often presents as a co-morbid condition with ME/CFS, we see that another zoonotic is implicated. This time it is Giardia lamblia, which was found to be the cause of both persistent IBS and chronic fatigue following an outbreak in Bergen, Norway in the autumn of 2004 [9,10]. Again we can see that a zoonotic is able to infect humans and cause symptoms common in ME/CFS.

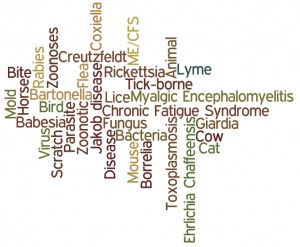

Commonly linked with ME/CFS

There are several other zoonotic pathogens that have been proposed to cause ME/CFS, or are often present as co-morbid infections. Some of the most commonly linked are Borrelia, Bartonella (Toxoplasmosis), Babesia, Coxiella burnetii, Rickettsia and Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Several ME/CFS researchers are looking at some of these zoonotics and investigating what role they might play in the pathology of the illness, so we have reason to be bullish about future progress in this area.

I will be reporting on some of these zoonotics in future articles in the series, so look out for the next article: Borrelia - in the Lyme Light.

Joel was diagnosed with ME/CFS in 2009 but struggled with the illness for some time prior to this. He loves to write, and hopes to regain enough health to return to the career he loved and have his novels published.

REFERENCES

1. Taylor et al. Risk factors for human disease emergence. philosophical transactions of the royal society of biological sciences. 2001.

2. Wells DL. Associations between pet ownership and self-reported health status in people suffering from chronic fatigue syndrome. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2009.

3. Gilliland SM et al. Investigation of porcine circovirus contamination in human vaccines. July 2012.

4. TARELLO W. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome in horses: diagnosis and treatment of cases. Comparative immunology microbiology and infectious diseases. 2001.

5. TARELLO W. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) in 15 dogs and cats with specific biochemical and microbiological anomalies. Comparative immunology microbiology and infectious diseases. 2001.

6. TARELLO W. Chronic Fatigue and Immune Dysfunction Syndrome associated with Staphylococcus spp. bacteremia responsive to thiacetarsamide sodium in eight birds of prey. Journal of Veterinary Medicine B. 2001.

7. TARELLO W. Etiologic Agents and Diseases Found Associated with Clinical Aspergillosis in Falcons. International Journal of Microbiology. 2011.

8. TARELLO W. Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) associated with Staphylococcus spp. bacteremia, responsive to potassium arsenite 0.5% in a veterinary surgeon and his coworking wife, handling with CFS animal cases. 2001.

9. Wood NJ. Infection: Giardia lamblia is associated with an increased risk of both IBS and chronic fatigue that persists for at least 3 years. 2011.

10. Wensaas KA et al. Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic fatigue 3 years after acute giardiasis: historic cohort study. 2012.

Suggested reading

- Zdenek Hubálek: Anthroponoses, Zoonoses, and Sapronoses. Journal: Emerging Human Infectious Diseases.

- Zoonoses – World Health Organisation

- CDC – National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases

- Clinical Knowledge Summaries: Tick-borne diseases (NICE – NHS)

- Table of Zoonotic Diseases and Organisms (UK Health Protection Agency)