Simon submitted a new blog post:

The power and pitfalls of omics part 2: epigenomics, transcriptomics and ME/CFS

Simon McGrath concludes his blog about the remarkable Prof George Davey Smith's smart ideas for understanding diseases, which may soon be applied to ME/CFS.

Last November, science star Professor George Davey Smith gave a talk at the UK CFS/ME Research Collaborative (CMRC) Annual Science Conference laying out ideas for bigger, better, smarter research. Although much of his talk wasn’t focused specifically on ME/CFS in particular, his points are of great interest to the ME/CFS community.

This is because Davey Smith has said he’s keen to play a role in the largest research set of studies ever proposed for ME/CFS: Professor Stephen Holgate’s Grand Challenge, which is now moving forward. Davey Smith is one of the most high-powered scientists to ever take on this disease.

Part 1 focused on his remarks about genomics-based research. This final part describes the promises and pitfalls of two other big-data omics approaches that are likely to be applied for the first time on a huge scale to ME/CFS, as part of the Grand Challenge. While genomics examines the DNA itself, these two approaches — epigenomics and transcriptomics — look at how the body makes use of that DNA.

Epigenetics: huge potential, or the confused researcher’s friend?

In his usual sceptical way, Davey Smith started by dousing overenthusiasm about this most fashionable of ’omics. He described epigenetics (epigenomics is just the large-scale study of epigenetics) as 'the confused researcher's friend’ — ‘if they ask you anything you don't know, just say it's due to epigenetics'.

He began with a quick primer on epigenetics. Almost every one of an organism’s cells contains essentially the same genetic blueprint, whether it's a kidney cell, a skin cell, or a brain cell. So some system is needed to tell a kidney cell to run the “kidney cell” portion of the DNA, not the “brain cell” portion.

Epigenetics is the main system that turns some genes on and some genes off long-term, without affecting the DNA sequence itself.

Not only do epigenetic changes affect cells long-term, they are also inherited when cells divide. In some cases, epigenetic changes are passed on to the organism’s offspring. For example, rats exposed to the main psychoactive component of cannabis during adolescence have offspring that are more likely to get addicted to heroin. And epigenetic changes — not changes to the DNA — are responsible for this. It’s less clear as to whether or no human epigenetic changes are passed on.

The two main types of epigenetic change:

DNA methylation (purple diamonds) and histone tail modification (triangles). Graphic: NIH

The most studied type of epigenetic change occurs when cells add a small chemical tag on genes that turns them down, or off. This is called “methylation.” It’s the most stable type of epigenetic change.

(Here’s a recent ME/CFS pilot study on methylation that now has funds for a much larger replication.)

Another way cells do this is by essentially packing some genes away in a closet. Since each minuscule human cell contains about 6 feet of DNA, cells have a system of proteins to wrap that long rope up into a tidy package and then to uncoil it in the spots that are needed.

Altering one of these proteins, known as histones, makes some genes easy to access and use, and some more difficult. That provides another mechanism for epigenetics to affect — which genes get transcribed, and which don't.

We know that epigenetic changes can perpetuate disease. Take the case of cirrhosis of the liver, a disease typically caused by alcohol abuse or the hepatitis C virus. Yet even if the cause is removed – say, the person stops drinking – the disease continues.

That’s because diseased liver cells have undergone epigenetic changes, and when diseased liver cells divide, said Davey Smith, they produce two sick cells: the new cells don’t revert to being healthy liver cells.

Epigenetic's role extends beyond switching cells into particular tissue types, and isn’t simply fixed at the cell’s creation, or merely linked. Environmental factors such as smoking can change the epigenetics of a cell after it’s been created.

Researchers have been pursuing this, linking epigenetic changes to environmental factors and to ill health. For example, a media-grabbing study claimed that holocaust survivors’ trauma was passed on to their children by inherited epigenetics. Another story, reported in the Daily Mail, claimed there was an epigenetic test “that reveals if you are gay.”

Most of this is hyped nonsense, Davey Smith said. The holocaust study, for example, was based on a ridiculously small sample of 22 survivors and nine controls. The story about homosexuality was based on just 49 pairs of twins, and the claimed accuracy of 70% isn’t so much better than tossing a coin.

The issues here are very similar to those discussed for genetics in Part 1. Cause and effect are difficult to tease out: are epigenetic changes associated with a disease the cause, or just an effect, of the disease? Furthermore, as with genetic association studies and Mendelian randomization, big sample sizes are essential for robust epigenetic findings.

The forensic epigenome: What our epigenome reveals about us

But epigenetics is important, and not just in making sure we don’t end up as a big blob of identical cells. And Davey Smith has led the way in teasing out solid findings.

A large population study he led showed that smoking by a mother during pregnancy left several clear epigenetic marks on the baby’s DNA at birth — some of which were still present 17 years later. Alcohol drinking as an adult leaves epigenetic fingerprints, too.

Davey Smith said that it was “utterly remarkable” that epigenetics can also accurately predict someone’s age to within a few years which, together with other epigenetic information, can be used to yield valuable information from DNA left at a crime scene. So you might be able to say someone was a 55-year-old heavy drinking ex-smoker, said Davey Smith. “But most 55-year-olds are heavy drinkers who used to smoke, so that may be of limited forensic value”, added the 55-year-old.

A new way to study disease in the lab?

Epigenetic changes could play a role in ME/CFS, and Davey Smith said that there was an intriguing way scientists could determine this — though it's not yet been done this way.

If scientists can identify epigenetic changes that are linked to a disease like ME/CFS, they could potentially use new technology to grow cells in the laboratory with those epigenetic changes, and see if they function differently.

If so, those changes may be driving the disease, and if not, they’re probably just irrelevant passengers along for the ride, as with vitamin E’s link with coronary heart disease. Davey Smith called this possible approach ‘very exciting’.

It relies on use of some very clever technology to turn blood cells into whatever cell types researchers want to study, even neurones. The NIH’s new ME/CFS study plans to use a similar approach to grow and investigate neurones in the lab, starting off with cells from patient blood (though they won’t be looking at epigenetics).

Gene expression (Transcriptomics)

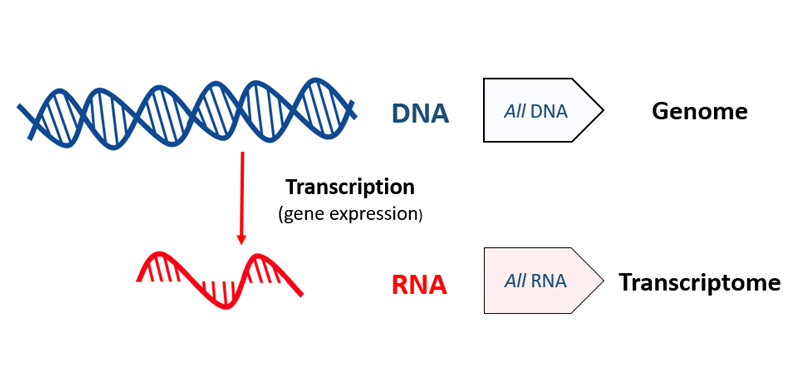

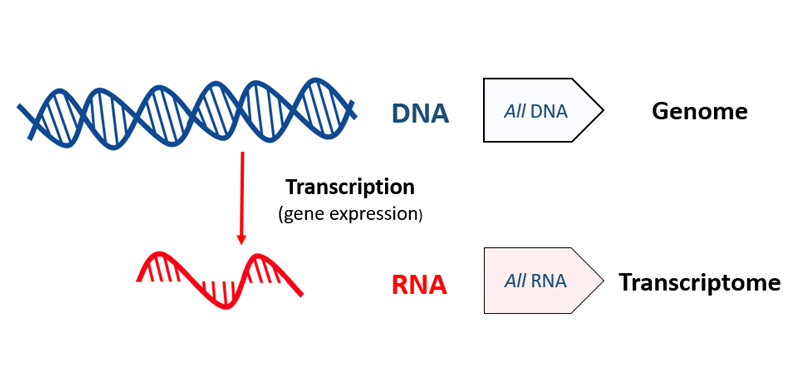

While genomics looks at all the DNA, the whole genome, transcriptomics looks at all the RNA.

While genomics looks at all the DNA, the whole genome, transcriptomics looks at all the RNA.

DNA/RNA graphic: openclipart.

To make use of DNA, cells must first copy (or transcribe) bits of it into RNA, a process known as gene expression, or transcription. So another way of studying which pieces of the DNA a cell is using most is to find all the RNA in a cell at a particular moment.

Studying all the RNA produced like this is called ‘transcriptomics’ (as opposed to some gene expression studies that just focus on the RNA transcribed from a limited set of genes).

Yet again, Davey Smith started with scepticism, calling transcriptomics ‘the over-hyped 'omics before epigenetics came along’. He pointed to the same litany of problems, with studies that were too small and ended up not replicating.

Some work has been done on gene expression in ME/CFS patients. One fascinating small study found distinct gene expression patterns in patients following a moderate exercise test, and those results have apparently been replicated in a larger study, but are yet to be published.

Davey Smith’s warning about size, however, applies to most gene expression studies in ME/CFS so far.

A second problem is that most gene expression studies only use white blood cells — because they are easy to access — rather than the most relevant tissue — such as liver cells — when studying liver disease. Perhaps surprisingly, there is actually some correlation between gene expression in blood cells and that in other tissues, but it’s not a good way to find out what’s going on in the biologically relevant tissues.

A powerful new transcriptomics resource

Davey Smith highlighted a new gene expression research project that has huge potential to overcome these problems, with the opportunity to probe the biological function of any genes that have been associated with disease.

The GTeX project has transcriptomics data for up to 50 different tissues — including the brain — from nearly 1,000 donors, which makes it something of a goldmine. Its ‘secret’ for accessing all tissues is that it measures gene expression in tissues taken from donors who had died only hours earlier (often in traffic accidents).

Crucially, this allows scientists to see how genes are expressed almost everywhere, even in the brain, so researchers can see what happens in tissue that is most relevant to a disease.

One of the great things about the GTeX project is that gene expression data in over 7,000 tissue samples (and growing fast) is ready to be accessed online. For the first time, researchers can search to see what a candidate gene implicated in a disease is actually doing in tissues across the body.

So if researchers identify gene differences that are implicated in ME/CFS, they can now simply dial into GTeX to see affect (if any) those gene differences have in different tissues. They can even look at the effect in the brain, an organ that is often implicated in the illness, but is normally impossible to study.

Two new ways to use omics to probe diseases, including ME/CFS

So Davey Smith highlighted two ingenious news ways to go from simply finding gene or epigenetic differences that are linked to a disease, to exploring their biological relevance.

Potentially, researchers could grow cells in the lab to investigate effects of epigenetic changes on function. And GTeX allows researchers to see the impact of gene differences on gene expression in any tissue in the body.

That could be a big step forward in understanding how changes in genes might cause many diseases, including ME/CFS.

Davey Smith clearly has a very sharp, innovative mind. And the good news is that's he's likely to be bringing his smart ideas to bear on ME/CFS, through the CMRC's Grand Challenge, which holds its first meeting in April.

Disclaimer: This blog is my take on Professor Davey Smith’s excellent talk, based on the YouTube video. The official summary of his talk, written by Emily Beardall with Action for ME, and approved by Davey Smith, is available to download here.

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research:

Continue reading the Original Blog Post

The power and pitfalls of omics part 2: epigenomics, transcriptomics and ME/CFS

Simon McGrath concludes his blog about the remarkable Prof George Davey Smith's smart ideas for understanding diseases, which may soon be applied to ME/CFS.

Last November, science star Professor George Davey Smith gave a talk at the UK CFS/ME Research Collaborative (CMRC) Annual Science Conference laying out ideas for bigger, better, smarter research. Although much of his talk wasn’t focused specifically on ME/CFS in particular, his points are of great interest to the ME/CFS community.

This is because Davey Smith has said he’s keen to play a role in the largest research set of studies ever proposed for ME/CFS: Professor Stephen Holgate’s Grand Challenge, which is now moving forward. Davey Smith is one of the most high-powered scientists to ever take on this disease.

Part 1 focused on his remarks about genomics-based research. This final part describes the promises and pitfalls of two other big-data omics approaches that are likely to be applied for the first time on a huge scale to ME/CFS, as part of the Grand Challenge. While genomics examines the DNA itself, these two approaches — epigenomics and transcriptomics — look at how the body makes use of that DNA.

Epigenetics: huge potential, or the confused researcher’s friend?

In his usual sceptical way, Davey Smith started by dousing overenthusiasm about this most fashionable of ’omics. He described epigenetics (epigenomics is just the large-scale study of epigenetics) as 'the confused researcher's friend’ — ‘if they ask you anything you don't know, just say it's due to epigenetics'.

He began with a quick primer on epigenetics. Almost every one of an organism’s cells contains essentially the same genetic blueprint, whether it's a kidney cell, a skin cell, or a brain cell. So some system is needed to tell a kidney cell to run the “kidney cell” portion of the DNA, not the “brain cell” portion.

Epigenetics is the main system that turns some genes on and some genes off long-term, without affecting the DNA sequence itself.

Not only do epigenetic changes affect cells long-term, they are also inherited when cells divide. In some cases, epigenetic changes are passed on to the organism’s offspring. For example, rats exposed to the main psychoactive component of cannabis during adolescence have offspring that are more likely to get addicted to heroin. And epigenetic changes — not changes to the DNA — are responsible for this. It’s less clear as to whether or no human epigenetic changes are passed on.

The two main types of epigenetic change:

DNA methylation (purple diamonds) and histone tail modification (triangles). Graphic: NIH

The most studied type of epigenetic change occurs when cells add a small chemical tag on genes that turns them down, or off. This is called “methylation.” It’s the most stable type of epigenetic change.

(Here’s a recent ME/CFS pilot study on methylation that now has funds for a much larger replication.)

Another way cells do this is by essentially packing some genes away in a closet. Since each minuscule human cell contains about 6 feet of DNA, cells have a system of proteins to wrap that long rope up into a tidy package and then to uncoil it in the spots that are needed.

Altering one of these proteins, known as histones, makes some genes easy to access and use, and some more difficult. That provides another mechanism for epigenetics to affect — which genes get transcribed, and which don't.

We know that epigenetic changes can perpetuate disease. Take the case of cirrhosis of the liver, a disease typically caused by alcohol abuse or the hepatitis C virus. Yet even if the cause is removed – say, the person stops drinking – the disease continues.

That’s because diseased liver cells have undergone epigenetic changes, and when diseased liver cells divide, said Davey Smith, they produce two sick cells: the new cells don’t revert to being healthy liver cells.

Epigenetic's role extends beyond switching cells into particular tissue types, and isn’t simply fixed at the cell’s creation, or merely linked. Environmental factors such as smoking can change the epigenetics of a cell after it’s been created.

Researchers have been pursuing this, linking epigenetic changes to environmental factors and to ill health. For example, a media-grabbing study claimed that holocaust survivors’ trauma was passed on to their children by inherited epigenetics. Another story, reported in the Daily Mail, claimed there was an epigenetic test “that reveals if you are gay.”

Most of this is hyped nonsense, Davey Smith said. The holocaust study, for example, was based on a ridiculously small sample of 22 survivors and nine controls. The story about homosexuality was based on just 49 pairs of twins, and the claimed accuracy of 70% isn’t so much better than tossing a coin.

The issues here are very similar to those discussed for genetics in Part 1. Cause and effect are difficult to tease out: are epigenetic changes associated with a disease the cause, or just an effect, of the disease? Furthermore, as with genetic association studies and Mendelian randomization, big sample sizes are essential for robust epigenetic findings.

The forensic epigenome: What our epigenome reveals about us

But epigenetics is important, and not just in making sure we don’t end up as a big blob of identical cells. And Davey Smith has led the way in teasing out solid findings.

A large population study he led showed that smoking by a mother during pregnancy left several clear epigenetic marks on the baby’s DNA at birth — some of which were still present 17 years later. Alcohol drinking as an adult leaves epigenetic fingerprints, too.

Davey Smith said that it was “utterly remarkable” that epigenetics can also accurately predict someone’s age to within a few years which, together with other epigenetic information, can be used to yield valuable information from DNA left at a crime scene. So you might be able to say someone was a 55-year-old heavy drinking ex-smoker, said Davey Smith. “But most 55-year-olds are heavy drinkers who used to smoke, so that may be of limited forensic value”, added the 55-year-old.

A new way to study disease in the lab?

Epigenetic changes could play a role in ME/CFS, and Davey Smith said that there was an intriguing way scientists could determine this — though it's not yet been done this way.

If scientists can identify epigenetic changes that are linked to a disease like ME/CFS, they could potentially use new technology to grow cells in the laboratory with those epigenetic changes, and see if they function differently.

If so, those changes may be driving the disease, and if not, they’re probably just irrelevant passengers along for the ride, as with vitamin E’s link with coronary heart disease. Davey Smith called this possible approach ‘very exciting’.

It relies on use of some very clever technology to turn blood cells into whatever cell types researchers want to study, even neurones. The NIH’s new ME/CFS study plans to use a similar approach to grow and investigate neurones in the lab, starting off with cells from patient blood (though they won’t be looking at epigenetics).

Gene expression (Transcriptomics)

DNA/RNA graphic: openclipart.

To make use of DNA, cells must first copy (or transcribe) bits of it into RNA, a process known as gene expression, or transcription. So another way of studying which pieces of the DNA a cell is using most is to find all the RNA in a cell at a particular moment.

Studying all the RNA produced like this is called ‘transcriptomics’ (as opposed to some gene expression studies that just focus on the RNA transcribed from a limited set of genes).

Yet again, Davey Smith started with scepticism, calling transcriptomics ‘the over-hyped 'omics before epigenetics came along’. He pointed to the same litany of problems, with studies that were too small and ended up not replicating.

Some work has been done on gene expression in ME/CFS patients. One fascinating small study found distinct gene expression patterns in patients following a moderate exercise test, and those results have apparently been replicated in a larger study, but are yet to be published.

Davey Smith’s warning about size, however, applies to most gene expression studies in ME/CFS so far.

A second problem is that most gene expression studies only use white blood cells — because they are easy to access — rather than the most relevant tissue — such as liver cells — when studying liver disease. Perhaps surprisingly, there is actually some correlation between gene expression in blood cells and that in other tissues, but it’s not a good way to find out what’s going on in the biologically relevant tissues.

A powerful new transcriptomics resource

Davey Smith highlighted a new gene expression research project that has huge potential to overcome these problems, with the opportunity to probe the biological function of any genes that have been associated with disease.

The GTeX project has transcriptomics data for up to 50 different tissues — including the brain — from nearly 1,000 donors, which makes it something of a goldmine. Its ‘secret’ for accessing all tissues is that it measures gene expression in tissues taken from donors who had died only hours earlier (often in traffic accidents).

Crucially, this allows scientists to see how genes are expressed almost everywhere, even in the brain, so researchers can see what happens in tissue that is most relevant to a disease.

One of the great things about the GTeX project is that gene expression data in over 7,000 tissue samples (and growing fast) is ready to be accessed online. For the first time, researchers can search to see what a candidate gene implicated in a disease is actually doing in tissues across the body.

So if researchers identify gene differences that are implicated in ME/CFS, they can now simply dial into GTeX to see affect (if any) those gene differences have in different tissues. They can even look at the effect in the brain, an organ that is often implicated in the illness, but is normally impossible to study.

Two new ways to use omics to probe diseases, including ME/CFS

So Davey Smith highlighted two ingenious news ways to go from simply finding gene or epigenetic differences that are linked to a disease, to exploring their biological relevance.

Potentially, researchers could grow cells in the lab to investigate effects of epigenetic changes on function. And GTeX allows researchers to see the impact of gene differences on gene expression in any tissue in the body.

That could be a big step forward in understanding how changes in genes might cause many diseases, including ME/CFS.

Davey Smith clearly has a very sharp, innovative mind. And the good news is that's he's likely to be bringing his smart ideas to bear on ME/CFS, through the CMRC's Grand Challenge, which holds its first meeting in April.

Disclaimer: This blog is my take on Professor Davey Smith’s excellent talk, based on the YouTube video. The official summary of his talk, written by Emily Beardall with Action for ME, and approved by Davey Smith, is available to download here.

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research:

Continue reading the Original Blog Post

Last edited by a moderator: