You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Simulate the PACE trial with a random number generator

- Thread starter wdb

- Start date

alex3619

Senior Member

- Messages

- 13,810

- Location

- Logan, Queensland, Australia

Hi wdb, very very amusing, maybe you should write a blog post on this with more info. Bye, Alex

Bob

Senior Member

- Messages

- 16,455

- Location

- England (south coast)

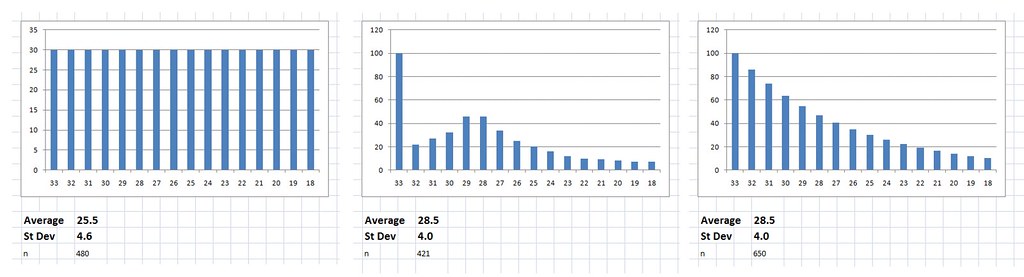

- Start with 600 cases with an initial fatigue score of 28.5

- Randomly increase the deviation of the scores to simulate some improving and some worsening, cap scores at 33 - the maximum possible fatigue score.

- Watch as the average score magically drops.

View attachment 5091

Hi wdb,

I don't understand the terms you've used, or exactly what you've done...

Would you mind explaining it in more detail please?

Thanks,

Bob

anciendaze

Senior Member

- Messages

- 1,841

Try that with 1,200 patients, call half of them optimists and half pessimists, based on experience in a period prior to the start of the study. Start your variation before the study itself. Exclude pessimists based on their score at the time approached to participate. See a difference? (1,200 is a round number estimate of the total participants, dropouts, and those who declined to participate.)

anciendaze

Senior Member

- Messages

- 1,841

random walks

Here's my explanation. I'm going to treat a patient's progress, with or without treatment, as a random walk caused by factors the patient does not control, most are outside the experimental protocol. At each step, for each patient, you flip a coin to decide whether to get better or worse. (In a more advanced random walk, the length of the step is also varied from zero to infinity, infinity being vanishingly improbable. Idealized random walks do not have bounds.) A discrete random walk with fixed step size will be enough to illustrate the bias. If you want to sound expert, you can call the random walk model a null hypothesis for treatment effectiveness.

Once you start running the simulation some patients will get better and some worse, no matter what else might be going on. You could think about them as diffusing away from the starting state like dye molecules in a pool of water. Wait long enough and diffusion will spread dye molecules from a single drop throughout a swimming pool.

Now, throw in that upper bound on fatigue scores. No matter how things change no score can get worse than 33. This is like a random walk hitting a wall. If nothing stops walks in the direction of zero fatigue, the mean score will inevitably drop as time progresses.

The same effect shows up if you simulate physical activity scores. In principle these could range from 0 to 65 within the trial. In practice patients with activity scores below 30 are unable to participate. Those above 60 (shouldn't this be 65?) are considered recovered.

Efforts to prevent adverse effects on patients were prominent in this trial, which complicates interpretation. There were lots of "adverse events", some "serious adverse events" and a few "adverse outcomes". "Adverse outcomes" which preferentially remove those with bad scores are a real statistical concern, but few are reported. Response to "adverse events" is more problematical.

If supportive measures not part of the treatment prevent scores from moving past a bound, we have the wall problem above. With several categories of problems leading to interventions, we have a complicated set of leaky barriers in place of a wall. If nothing prevents random walks from passing a bound and being treated as recoveries, while interventions prevent most adverse outcomes, we have a fundamental bias built into the protocol, (or at least the way it is implemented.) Interventions, and ways of dealing with bounds, become more important than any treatment.

Here's my explanation. I'm going to treat a patient's progress, with or without treatment, as a random walk caused by factors the patient does not control, most are outside the experimental protocol. At each step, for each patient, you flip a coin to decide whether to get better or worse. (In a more advanced random walk, the length of the step is also varied from zero to infinity, infinity being vanishingly improbable. Idealized random walks do not have bounds.) A discrete random walk with fixed step size will be enough to illustrate the bias. If you want to sound expert, you can call the random walk model a null hypothesis for treatment effectiveness.

Once you start running the simulation some patients will get better and some worse, no matter what else might be going on. You could think about them as diffusing away from the starting state like dye molecules in a pool of water. Wait long enough and diffusion will spread dye molecules from a single drop throughout a swimming pool.

Now, throw in that upper bound on fatigue scores. No matter how things change no score can get worse than 33. This is like a random walk hitting a wall. If nothing stops walks in the direction of zero fatigue, the mean score will inevitably drop as time progresses.

The same effect shows up if you simulate physical activity scores. In principle these could range from 0 to 65 within the trial. In practice patients with activity scores below 30 are unable to participate. Those above 60 (shouldn't this be 65?) are considered recovered.

Efforts to prevent adverse effects on patients were prominent in this trial, which complicates interpretation. There were lots of "adverse events", some "serious adverse events" and a few "adverse outcomes". "Adverse outcomes" which preferentially remove those with bad scores are a real statistical concern, but few are reported. Response to "adverse events" is more problematical.

If supportive measures not part of the treatment prevent scores from moving past a bound, we have the wall problem above. With several categories of problems leading to interventions, we have a complicated set of leaky barriers in place of a wall. If nothing prevents random walks from passing a bound and being treated as recoveries, while interventions prevent most adverse outcomes, we have a fundamental bias built into the protocol, (or at least the way it is implemented.) Interventions, and ways of dealing with bounds, become more important than any treatment.

Bob

Senior Member

- Messages

- 16,455

- Location

- England (south coast)

OK, I didn't understand any of this, so I asked a friend who knows about statistics, and he put it in layman's terms for me... So I thought I'd share it...

The way it works is simple enough. Imagine you are throwing 3 darts at a piece of paper which is only marked with the numbers 1 to 10. If you are good, perhaps your average score, for three darts, is 26. Let's say, for argument's sake that you don't become more skillful. As you continue to throw the darts, your average score is pretty certain to drop, because although you can improve your score a only a little bit (from 26 up to a maximum of 30), you can do a lot lot worse.

It's the opposite way around with these ME scores. If the average score is 28.5 out of 33, then any random changes, even from day to day, are bound to bring the score down, because there isn't much room to increase the score, but there is a lot of room to decrease it.

It isn't standard practice to make allowances for this effect because the situation isn't standard. It is caused simply by the lack of ability to move the results very far in one direction.

Here's another simple illustration - back to the darts: two players both score 27 (out of 30), on the next round one player gets much better and boosts the score up to 30 (which is as good as he can go), the other gets much worse and scores 20. The average has now dropped to 25.

It is possible that the treatment made some patients worse, but with a score of 28.5 out of 33, you can't get much worse. But some can get a lot better. The dice are loaded. It isn't the fact that the average is moved by deviation, it's just that it only has room really to move one way.

The bit about "randomly increase the deviation" refers to how much change in the scores is likely on average. If the average score is 28.5 out of 33, then if most people only change their score by 1 or 2 points, it is fair. But if some of them start to change their scores by 5 or more, then improvement starts to have a bigger effect than deterioration, just because bigger changes are only possible for those that improve.

And so, from your graph, wdb, it seems that if the random deviation increases by 10 points on the Chalder scale, then the average fatigue scores would naturally decrease by about 5 points, but without any actual improvement in the average general fatigue levels. The average fatigue scores would decrease when there was a natural random deviation from the original fatigue scores, even if the actual average general fatigue levels stayed the same.

(Have i got that right?)

The way it works is simple enough. Imagine you are throwing 3 darts at a piece of paper which is only marked with the numbers 1 to 10. If you are good, perhaps your average score, for three darts, is 26. Let's say, for argument's sake that you don't become more skillful. As you continue to throw the darts, your average score is pretty certain to drop, because although you can improve your score a only a little bit (from 26 up to a maximum of 30), you can do a lot lot worse.

It's the opposite way around with these ME scores. If the average score is 28.5 out of 33, then any random changes, even from day to day, are bound to bring the score down, because there isn't much room to increase the score, but there is a lot of room to decrease it.

It isn't standard practice to make allowances for this effect because the situation isn't standard. It is caused simply by the lack of ability to move the results very far in one direction.

Here's another simple illustration - back to the darts: two players both score 27 (out of 30), on the next round one player gets much better and boosts the score up to 30 (which is as good as he can go), the other gets much worse and scores 20. The average has now dropped to 25.

It is possible that the treatment made some patients worse, but with a score of 28.5 out of 33, you can't get much worse. But some can get a lot better. The dice are loaded. It isn't the fact that the average is moved by deviation, it's just that it only has room really to move one way.

The bit about "randomly increase the deviation" refers to how much change in the scores is likely on average. If the average score is 28.5 out of 33, then if most people only change their score by 1 or 2 points, it is fair. But if some of them start to change their scores by 5 or more, then improvement starts to have a bigger effect than deterioration, just because bigger changes are only possible for those that improve.

And so, from your graph, wdb, it seems that if the random deviation increases by 10 points on the Chalder scale, then the average fatigue scores would naturally decrease by about 5 points, but without any actual improvement in the average general fatigue levels. The average fatigue scores would decrease when there was a natural random deviation from the original fatigue scores, even if the actual average general fatigue levels stayed the same.

(Have i got that right?)

Given that we know the entry requirement was 6 out of 11 on the Chalder scale (equivalent to 18 out of 33) and that the initial average was 28.5 with standard deviation of 4, we can make a guess as to the initial distribution of scores.

We know the scores are not evenly distributed as this would give an average of 25.5, to get an average of 28.5 it has to be quite top heavy, something along the lines of the 2nd two distributions in the attachment.

Either way there must be a lot of cases initially scoring 33 or close to 33 who would have been unable to measure any significant worsening of their condition, and these would be the most severely affected patients who would presumably be the most likely to experience worsening.

We know the scores are not evenly distributed as this would give an average of 25.5, to get an average of 28.5 it has to be quite top heavy, something along the lines of the 2nd two distributions in the attachment.

Either way there must be a lot of cases initially scoring 33 or close to 33 who would have been unable to measure any significant worsening of their condition, and these would be the most severely affected patients who would presumably be the most likely to experience worsening.

anciendaze

Senior Member

- Messages

- 1,841

That seems like a fair explanation, though we still have the 'natural boundary' of people with high fatigue scores or low activity scores either refusing to participate or failing to complete. I'm still thinking about ways to incorporate selection bias caused by this effect. Interventions to avoid adverse outcomes (ostensibly for the protection of patients) represent another possible source. The interventions could be more important than the specific treatment.

Bob

Senior Member

- Messages

- 16,455

- Location

- England (south coast)

That seems like a fair explanation, though we still have the 'natural boundary' of people with high fatigue scores or low activity scores either refusing to participate or failing to complete. I'm still thinking about ways to incorporate selection bias caused by this effect. Interventions to avoid adverse outcomes (ostensibly for the protection of patients) represent another possible source. The interventions could be more important than the specific treatment.

anciendaze, do you know if there were interventions during the trial due to adverse events etc? that seems like quite a significant thing to highlight.

Bob

Senior Member

- Messages

- 16,455

- Location

- England (south coast)

anciendaze

Senior Member

- Messages

- 1,841

After a misunderstanding and a blunder, when I did not check something I thought I remembered, I've become more cautious about checking memory. I recall quite a number of adverse events. The protocol requires checking on these, and trying to resolve problems. Naturally they would encourage patients to remain in the study at the same time. We don't know exactly what went on in these cases.anciendaze, do you know if there were interventions during the trial due to adverse events etc? that seems like quite a significant thing to highlight.

There is another problem with words. In medical research literature, an intervention can mean something as dramatic as a heart transplant. The entire therapy applied to a group is technically an intervention in an illness. I'm using the word in a less specific sense. Patients who experienced adverse events had more interactions with research nurses than those without. The number of events reported is high enough to make this as significant as other aspects of the treatment. Since they only intervene to prevent adverse outcomes, this creates a substantial bias.

Bob

Senior Member

- Messages

- 16,455

- Location

- England (south coast)

After a misunderstanding and a blunder, when I did not check something I thought I remembered, I've become more cautious about checking memory.

Tell me about it!

I recall quite a number of adverse events. The protocol requires checking on these, and trying to resolve problems. Naturally they would encourage patients to remain in the study at the same time. We don't know exactly what went on in these cases.

There is another problem with words. In medical research literature, an intervention can mean something as dramatic as a heart transplant. The entire therapy applied to a group is technically an intervention in an illness. I'm using the word in a less specific sense. Patients who experienced adverse events had more interactions with research nurses than those without. The number of events reported is high enough to make this as significant as other aspects of the treatment. Since they only intervene to prevent adverse outcomes, this creates a substantial bias.

OK, thanks for that anciendaze.

These patients had far more input than anyone would have in a normal NHS setting anyway.

I'm sure that they had many hours of one to one encouragement, that you wouldn't get in a normal setting.

I haven't yet found out exactly how many hours of SMC and GET and other encouragement and instructions they had... It would be interesting to find out.

I noticed that in the protocol they say " A score of 70 is about one standard deviation below the mean score (about 85, depending on the study) for the UK adult population.

but in the paper they say " the mean minus 1 SD scores of the UK working age population of 84 (-24) for physical function (score of 60 or more).

So 1 standard deviation changed from 15 to 24 in the course of the study!

The final paper only refers to

33 Bowling A, Bond M, Jenkinson C, Lamping DL. Short form 36

(SF-36) health survey questionnaire: which normative data should

be used? Comparisons between the norms provided by the

Omnibus Survey in Britain, The Health Survey for England and

the Oxford Healthy Life Survey. J Publ Health Med 1999, 21: 25570.

and dropped

.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, L W: Short form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey questionnaire: normative data from a large random sample of working age adults. BMJ 1993, 306:1437-1440. Free full text: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1677870

Mithriel

but in the paper they say " the mean minus 1 SD scores of the UK working age population of 84 (-24) for physical function (score of 60 or more).

So 1 standard deviation changed from 15 to 24 in the course of the study!

The final paper only refers to

33 Bowling A, Bond M, Jenkinson C, Lamping DL. Short form 36

(SF-36) health survey questionnaire: which normative data should

be used? Comparisons between the norms provided by the

Omnibus Survey in Britain, The Health Survey for England and

the Oxford Healthy Life Survey. J Publ Health Med 1999, 21: 25570.

and dropped

.Jenkinson C, Coulter A, L W: Short form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey questionnaire: normative data from a large random sample of working age adults. BMJ 1993, 306:1437-1440. Free full text: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1677870

Mithriel

anciendaze

Senior Member

- Messages

- 1,841

This is one reason I have trouble remembering what I read in it. Words and numbers keep changing meaning. Contradictions like this cause my mental model of what they are saying to evaporate....So 1 standard deviation changed from 15 to 24 in the course of the study!l

I noticed that in the protocol they say " A score of 70 is about one standard deviation below the mean score (about 85, depending on the study) for the UK adult population.

but in the paper they say " the mean minus 1 SD scores of the UK working age population of 84 (-24) for physical function (score of 60 or more).

So 1 standard deviation changed from 15 to 24 in the course of the study!

Even worse in fact, this study:

Chronic Fatigue Syndrome A clinically empirical approach to its definition and study

Found healthy controls to have an SP-36 Physical function score of 89.7 SD 13.2 (table 6)

making 1 SP below average 76.5