View the Post on the Blog

Hooked up for a CPET

Simon McGrath reports on Dr Snell's new study demonstrating that ME/CFS patients have a reduced capacity to exercise when they repeat a maximum exercise test one day on - unlike healthy controls.

One of the biggest problems of getting ME/CFS taken seriously is that often we 'look' normal, even though we feel lousy, and most lab tests produce 'normal' findings. How do we prove to the world that we are sick?

A defining feature of ME/CFS is Post-Exertional Malaise (PEM) and a couple of studies have clearly demonstrated PEM in patients [see box]. However, PEM is a subjective experience and one that can only be measured by patient self-report, which won't satisfy everyone.

Dr Chris Snell, Staci Stevens, Dr Todd Davenport, and Dr Mark VanNess's new study aimed to objectively demonstrate the problem of post-exertional malaise, by using a repeat Cardiopulmonary Exercise Test (CPET). As they formally hypothesized in their paper: "an exacerbation of symptoms following the first test would be reflected in physiological responses to the second".

The study

The 51 CFS patients were all women, met Fukuda criteria and also reported PEM. Controls, also female, were similar in age and BMI, and were fairly sedentary. In fact, the results of the first CPET revealed that the controls were in the bottom 10% of published population norms and would count as deconditioned. CFS patients were barely different from controls so were also deconditioned, but, crucially, they were ill while controls were healthy, casting doubt on the idea that deconditioning is responsible for CFS.

CPET: Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing explained

CPET is the Gold standard for measuring physical capacity, used by athletes wanting to measure the effectiveness of their training programs. It's also used medically e.g. to diagnose cardiovascular, breathing and muscle disorders.

The principle is to get someone to exercise to exhaustion, using a protocol that starts easy and gets increasingly difficult until the subject can do no more. The key measures for this study are the Volume of Oxygen consumed (VO2) and the amount of work done, measured in Watts on the exercise bike.

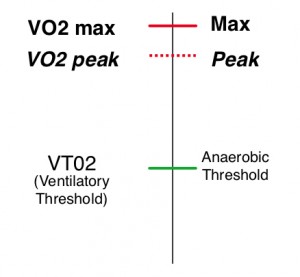

Anaerobic/Ventilatory Threshold

A critical factor is the anaerobic threshold, the point at which the body has to supplement normal aerobic (oxygen-burning) metabolism with much less efficient anaerobic metabolism, creating lactic acid. This threshold is measured in CPET by finding the point where carbon dioxide (CO2) starts to be produced faster than Oxygen, and is called the Ventilatory Threshold, or VT (strictly, VO2 VT).

VO2 max versus VO2 peak

One challenge of CPET is detecting if the person is using maximal effort, as opposed to trying pretty hard. Data showed that CFS patients and subjects here all went deep into anaerobic exercise and met at least one other measure of high effort. However, as it's almost impossible to be completely sure, the study reported 'peak' measures instead of maximum, e.g. VO2 peak, not VO2 max.

Note there are equivalent thresholds for work output, in watts: W max, W peak and W VT

More: Lannie's blog on PR about her CPET at Pacific Fatigue Labs.

Day 2 results separated patients from controls

A Day 2 CFS patient...

The big differences between the groups emerged on the second maximal CPET test, 24 hours after the first. On average, controls did slightly better on Day 2 (something that has been observed in other studies too) while patients did substantially worse. Interestingly, VO2 peak did not differ significantly between patients and controls, but peak Watts output was significantly lower, as was VTO2 . The biggest difference of all was for Watts output at VT, down for the patient group by over half.

The study found the repeat test could separate CFS patients from controls in this sample with 95% accuracy (3 errors in total). They also used a statistical technique called 'cross-validation', which indicated the test would achieve a 90% accuracy in an independent sample (though see issue with convenience sample below).

This ability of a 2-day repeat test to discriminate healthy but sedentary controls from CFS patients is critical. In theory, doctors can manage this easily enough without a CPET test. However, where there is doubt about the reality of symptoms, as can happen with disability insurance claims, an objective test can demonstrate that a patient really is sick. As Workwell Foundation notes, it's useful in legal or medical disputes; the reduced performance on VT is "impossible to fake", adds Dr Snell.

The study conclusion said:the post-exertional state in CFS is characterized by objectively measurable deficits in submaximal metabolism and workload that would be nearly impossible for patients to fabricate

In some ways the findings are unexpected, as it was the same group's earlier finding of a substantial drop in VO2 max on the second test that caused such a buzz amongst patients. And the big drop in output at VT wasn't seen in a study (albeit a small one) by a separate research group, though a smaller drop was seen for VT, and VO2 max in a study presented at an IACFS conference. I asked Chris Snell if he was surprised by the finding. "No", came the reply: the initial study was small making the findings less robust, and he said that a much bigger effect on VT than VO2 max has been seen in the clinic too.

Evidence of Post-Exertional Malaise from subjective studiesAs well as the objective evidence from this new paper, PEM has been shown by self-report measures too. A 2010 study from Pacific Fatigue Labs found that only 1 of 25 female CFS patients recovered from a maximal exercise test 48 hours later while all 23 sedentary controls did. Another study using a moderate exercise test found that fatigue and pain increased in the 48 hours after exercise in CFS patients - while it returned to normal in that time for both healthy controls and Multiple Sclerosis patients.

Committed to Maximal CPET

Given that it's hard enough for people with ME/CFS to do one maximal test, let alone two, these results create the temptation to just run the second test as far as the Ventilatory Threshold and forget about VO2 max. But Chris Snell stressed that the Workwell Foundation remains committed to the repeat-maximal approach. First, VT can't be measured on the fly so they wouldn't know when to stop the test. And perhaps more importantly, the post-exertional effect appears to differ by patient, with some showing a greater effect on peak measures and others at VT. Dr Snell suggested that varying post-exertional responses may well reflect different underlying pathologies.

Unique to ME/CFS?

Is this the killer test that uniquely identifies CFS patients? Dr Snell has reported that their clinic has tested patients with numerous illnesses including Multiple Sclerosis and Congestive heart failure, but have only seen the problem in ME/CFS patients. Published studies show normal repeat CPET performance for sarcoidosis, angina, Chronic Airflow Obstruction, Pulmonary Hypertension and heart disease. I’ve seen no studies showing failure to reproduce CPET results in other illnesses, but it’s probably too soon to say if this is unique to ME/CFS, or just very unusual.

What might cause the exercise problems?

The authors suggest that a synergy of small effects across multiple systems could be responsible for the poor exercise performance of the individuals with CFS. Lower oxygen carrying capacity could result from low blood volume, while low oxygen consumption could also result from autonomic dysfunction and reduced ventilation. But research into the causes is needed.

No study is perfect...

These findings, which make visible the hallmark ME/CFS problem of post-exertional malaise, have potentially huge importance. Replication of this study, perhaps with a more representative sample of CFS patients and some sick controls, should in my view be a priority for the research community. Stage two of the huge CDC multi-clinic study could provide the perfect opportunity for this.

- There were only 10 controls, though as the repeatability of CPET results is firmly established (with 94% reliability between tests), in some ways controls mainly serve to demonstrate that the protocol and equipment is working properly.

- The CFS patients were a convenience sample, rather than, for example, consecutive referrals to a secondary clinic. This, and the fact that patients had agreed to a repeat maximal exercise test, means the results might not generalize to the patient population as a whole.

- The earlier study by this group, and the other studes from independent groups, didn't find the dramatic changes with workload at the ventilatory threshold, so further replication would help to confirm the nature of the changes.

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 c.(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. and we'd love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help then please contact Mark through the Forum.

And don't forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online! To find out more, visit Phoenix Rising’s Donate page by clicking the button below.

View the Post on the Blog