CURRENT MEDICAL DIAGNOSIS & TREATMENT

Author: Stephen McPhee, MD, Maxine Papadakis, MD

Publisher: McGraw Hill

Publication Date: 2009

FATIGUE & CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

As an isolated symptom, fatigue accounts for 13% of visits to generalists. The symptom of fatigue may be less well defined and explained by patients than symptoms associated with specific functions. Fatigue or lassitude and the closely related complaints of weakness, tiredness, and lethargy are often attributed to overexertion, poor physical conditioning, sleep disturbance, obesity, undernutrition, and emotional problems. A history of the patients daily living and working habits may obviate the need for extensive and unproductive diagnostic studies.

CLINICAL FINDINGS

A. Fatigue

Clinically relevant fatigue is composed of three major components: generalized weakness (difficulty in initiating activities); easy fatigability (difficulty in completing activities); and mental fatigue (difficulty with concentration and memory). Important diseases that can cause fatigue include hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, CHF, infections (endocarditis, hepatitis), COPD, sleep apnea, anemia, autoimmune disorders, and cancer. Alcoholism, drug side effects such as from sedatives and β-blockers, and psychological conditions (such as insomnia, depression, and somatization disorder) are other causes. Common outpatient infective causes include mononucleosis and sinusitis. These conditions are usually associated with other characteristic signs, but patients may emphasize fatigue and not reveal their other symptoms unless directly asked. The lifetime prevalence of significant fatigue (present for at least 2 weeks) is about 25%. Fatigue of unknown cause or related to psychiatric illness exceeds that due to physical illness, injury, medications, drugs, or alcohol. Psychiatric disorders associated with fatigue include depression, dysthymia, somatoform disorders, panic attack, and alcohol abuse. Prolonged fatigue is a central feature of several syndromes, such as irritable bowel syndrome and anxiety.

B. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

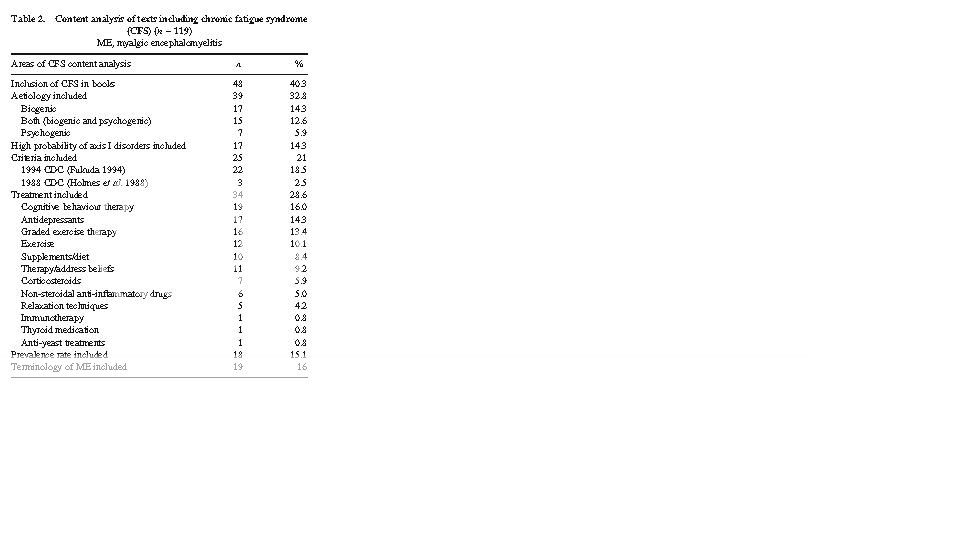

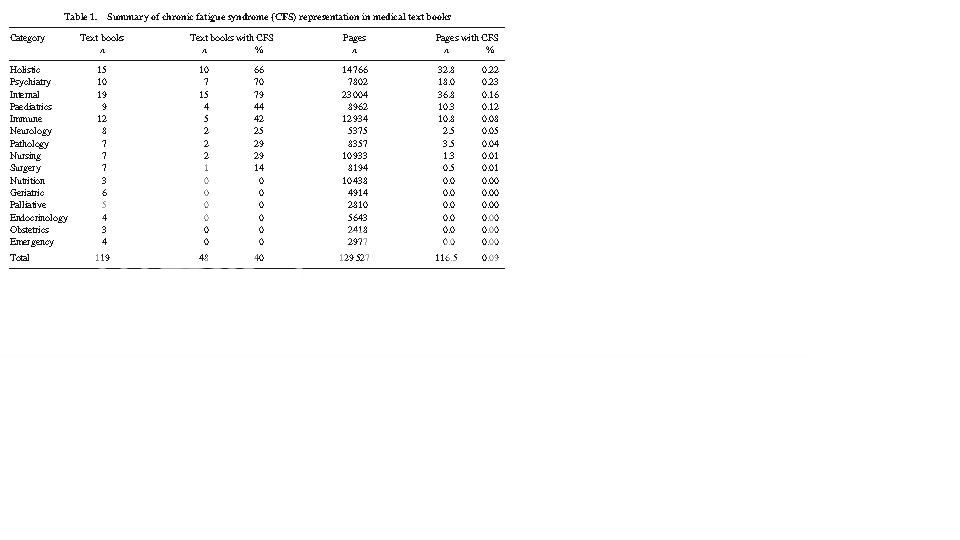

A working case definition of chronic fatigue syndrome indicates that it is not a homogeneous abnormality, and there is no single pathogenic mechanism (Figure 22). No physical finding or laboratory test can be used to confirm the diagnosis of this disorder.

With regard to its pathophysiology, early theories postulated an infectious or immune dysregulation mechanism. Persons with confirmed chronic fatigue syndrome report a much greater frequency of childhood trauma and psychopathology and demonstrate higher levels of emotional instability and self-reported stress than non-fatigued controls. Neuropsychological, neuroendocrine, and brain imaging studies have confirmed the occurrence of neurobiologic abnormalities in most patients. Sleep disorders have been reported in 4080% of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, but their treatment has provided only modest benefit, suggesting that it is an effect rather than a cause of the fatigue. MRI scans may show brain abnormalities on T2-weighted imageschiefly small, punctate, sub-cortical white matter hyperintensities, predominantly in the frontal lobes. Veterans of the Gulf War show a tenfold greater incidence of chronic fatigue syndrome compared with nondeployed military personnel.

In evaluating chronic fatigue, after the history and physical examination process is completed, standard investigation includes complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, serum chemistriesblood urea nitrogen (BUN), electrolytes, glucose, creatinine, and calcium; liver and thyroid function testsantinuclear antibody, urinalysis, and tuberculin skin test; and screening questionnaires for psychiatric disorders. Other tests to be performed as clinically indicated are serum cortisol, rheumatoid factor, immunoglobulin levels, Lyme serology in endemic areas, and tests for HIV antibody. More extensive testing is usually unhelpful, including antibody to Epstein-Barr virus. There may be an abnormally high rate of postural hypotension; some of these patients report response to increases in dietary sodium as well as antihypotensive agents such as fludrocortisone, 0.1 mg/d.

TREATMENT

A. Fatigue

Management of fatigue involves identification and treatment of conditions that contribute to fatigue, such as cancer, pain, depression, disordered sleep, weight loss, and anemia. Resistance training and aerobic exercise lessens fatigue and improves performance for a number of chronic conditions associated with a high prevalence of fatigue, including CHF, COPD, arthritis, and cancer. Continuous positive airway pressure is an effective treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Psychostimulants such as methylphenidate have shown inconsistent results in randomized trials of treatment of cancer-related fatigue.

B. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

A variety of agents and modalities have been tried for the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. Acyclovir, intravenous immunoglobulin, nystatin, and low-dose hydrocortisone/fludrocortisone do not improve symptoms. There is a greater prevalence of past and current psychiatric diagnoses in patients with this syndrome. Affective disorders are especially common, but fluoxetine alone, 20 mg daily, is not beneficial. Patients with chronic fatigue syndrome have benefited from a comprehensive multidisciplinary intervention, including optimal medical management, treating any ongoing affective or anxiety disorder pharmacologically, and implementing a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral treatment program. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, a form of nonpharmacologic treatment emphasizing self-help and aiming to change perceptions and behaviors that may perpetuate symptoms and disability, is helpful. Although few patients are cured, the treatment effect is substantial. Response to cognitive-behavioral therapy is not predictable on the basis of severity or duration of chronic fatigue syndrome, although patients with low interest in psychotherapy rarely benefit. Graded exercise has also been shown to improve functional work capacity and physical function. At present, intensive individual cognitive-behavioral therapy administered by a skilled therapist and graded exercise are the treatments of choice for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.

In addition, the clinicians sympathetic listening and explanatory responses can help overcome the patients frustrations and debilitation by this still mysterious illness. All patients should be encouraged to engage in normal activities to the extent possible and should be reassured that full recovery is eventually possible in most cases.