Simon submitted a new blog post:

Surprisingly good outcomes for people who get ME/CFS after Mononucleosis (Glandular Fever)

"When will this end?" It's a question that most ME/CFS patients have probably asked themselves and their doctor many times. I certainly have.

Yet there is astonishingly little hard data on recovery rates from this illness or on how much patients improve, and the evidence there is doesn't give too much hope.

Step forward a long-term follow-up study that shows unexpectedly good rates of improvement for younger people who developed ME/CFS after infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever) – though the results are hardly spectacular.

Around 11 years on from getting sick, just over half of all ME/CFS patients were able to work part or full-time, though fatigue levels remained high:

The study was led by Dr. Morten Nyland and comes from the Neurology department of Haukeland University Hospital in Norway, site of the famed Rituximab pilot study. In fact two of the authors of this new paper were part of that pilot study. And although this wasn't a trial, patients were encouraged to use self-management (pacing/activity management), and the authors concluded that this probably contributed to the relatively good outcomes.

How the study worked (important)

An ideal study would take a bunch of patients and follow them at consistent time points, say the start of the illness, and then five and 10 years later. In this case, though, researchers made the most of pre-existing data to access a large group of patients who were followed up at very different times in their illness, an approach using two contact points that still yields invaluable results.

"Contact 1" was the first time the patient was seen by the specialist ME/CFS clinic at Haukeland University Hospital, any time between 1996 and 2006.

"Contact 2" was a follow-up questionnaire sent to all patiets in 2009, an average of 6.5 years later. There was huge variation in follow-up time between patients, for example at the second and final contact in 2009 one patient had been ill for 24 years and another only five years. The study had data at both contact points for 92 patients, making this one of the largest follow-up studies going.

At the initial contact, patients had been ill for an average of nearly five years, and again that hides a lot of variation. Half had been ill for 3.2 years or less, a quarter for under two years. The higher average was because some had been ill for a very long time. The patients were also relatively young (the average age was 24 years), reflecting the age profile of infectious mononucleosis, the 'kissing disease', which particularly affects young adults and teens.

Over half of all patients were employed at final contact

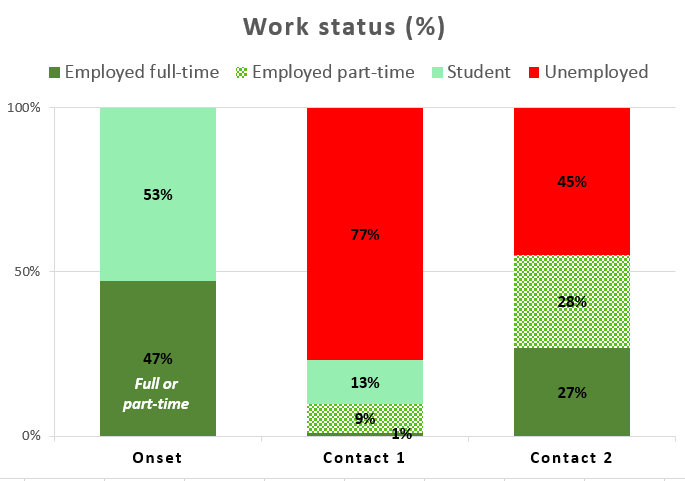

Pleasingly, the study used employment status as the clear-cut, objective primary outcome -- and arguably the ability to earn a living is the outcome that matters most to patients. The graph below shows a lot of improvement between first and second contact, which an average gap of six years, though the gap will vary a lot between patients.

Unemployment is in red while employment (full-time or part-time) or being a student is in green. Onset is when they got ill, Contact 1 is typically five years later, and Contact 2 typically another six years on.

Clearly things have improved for many patients, but the overall situation at Contact 2 remains a great deal worse than onset.

Note that half of those employed at Contact 2 were working full-time, compared with only 1 in 10 at Contact 1, so presumably there has been an increase in hours worked per person, as well as more people working.

Caution: It's possible that 11 years from onset (age 35 vs. age 24 at onset) some people would not be working anyway due to raising families so unemployment might not be zero even for a healthy group. And employment at onset wasn't split into full-time/part-time.

How patients said their overall health had changed

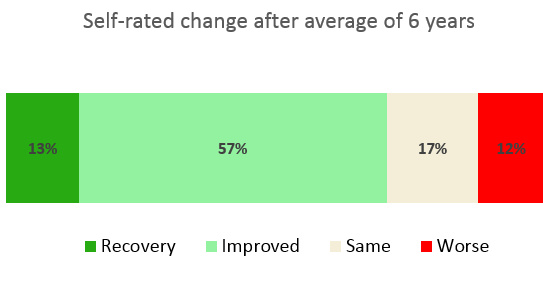

The study also asked patients how their overall health had changed since Contact 1 (their first visit to the clinic). Most patients said they had improved, 12% reported they had got worse.

Fatigue was also rated at both Contact 1 and Contact 2 using the Fatigue Severity Scale which gives an average score ranging from 1.0 (no fatigue) to 7.0 (maximum fatigue); any score of 5.0 or higher counts as severe fatigue. The average score at Contact 1 was 6.4, falling to 5.0 at Contact 2 -- so even after this improvement the group as a whole was right on the threshold of severe fatigue.

Different degrees of improvement

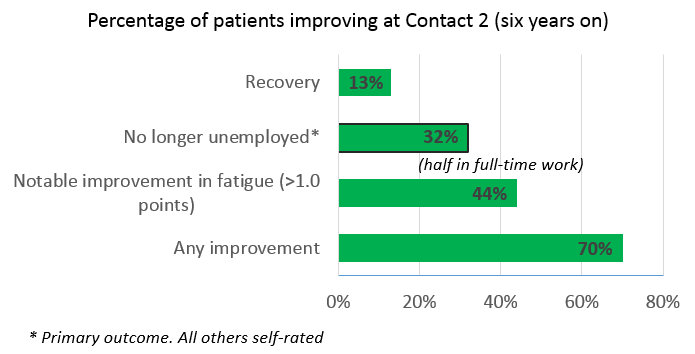

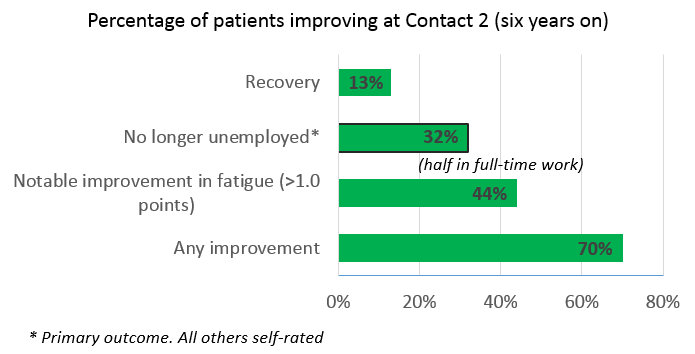

The study measured 'improvement' in several different ways. As well as change in employment status, they looked at self-rated improvement (including an option of 'recovered') and change in fatigue scores.

You can see that 'improvement' ranged from 70% reporting any improvement, to 32% moving into employment, and 13% who rated themselves as recovered.

Most people improved, even those who hadn't improved at Contact 1.

Another encouraging point was that of the 26 people who said they had already improved at Contact 1, 25 improved again by Contact 2. And of the 38 who reported they hadn't improved before, 25 (66%) improved by Contact 2.

Fatigue improved much less than employment status

One slightly strange finding, which the authors didn't comment on, is that average fatigue levels fall rather modestly compared with the percentage improving in employment status. While 32% of patients were able to start working, fatigue scores only fell from 6.4 to 5.0.

It seems likely that this in part is down to people getting back to work but still struggling, so that their level of fatigue doesn't improve as much as it might.

Interestingly, although 28% were working full-time only 13% rated themselves as 'recovered', which supports the view that some people are improving and choosing to work full-time despite not being completely well, and may still be struggling quite a lot.

What 'predicts' return to work/improvement over time? (not a lot)

Overall, this important new study shows that outcomes for younger people who develop ME/CFS after mono are not great, but are probably better than expected. Around half were in work 11 years after onset, though fatigue remains high for most.

What might be driving this improvement? The authors ran some fancy analysis to see what features (such as symptoms and age) predicted being in employment or an improved fatigue score at the final contact. It turned out that only lower joint pain at Contact 1 was associated with later employment, but the effect was small.

Similarly, low joint pain and depression at Contact 1, and better eduction, were predictors of less fatigue at Contact 2 -- but again the effect was small.

Surprisingly, length of illness was not an important predictor of employment or fatigue. Generally those with shorter illnesses are seen as having a better chance of recovery, but that doesn't appear to have been the case here.

It's possible that outcomes for ME/CFS after mono are better than after other triggers. I'll give the last word to the authors themselves, who suggest that both pacing/activity management and financial support through sickness benefits were likely to have played an important role to improvements:

Phoenix Rising thread discussing this paper, including the more detailed post that led to this blog.

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 c.(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. We’d also love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help in any way then please contact Mark through the Forums.

And don’t forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online! To find out more, visit Phoenix Rising’s Donate page by clicking the button below.

Continue reading the Original Blog Post

Surprisingly good outcomes for people who get ME/CFS after Mononucleosis (Glandular Fever)

Sometimes ME/CFS emerges after mononucleosis, or glandular fever. Simon McGrath shares results from a long-term follow-up study from Haukeland University Hospital in Norway...

"When will this end?" It's a question that most ME/CFS patients have probably asked themselves and their doctor many times. I certainly have.

Yet there is astonishingly little hard data on recovery rates from this illness or on how much patients improve, and the evidence there is doesn't give too much hope.

Step forward a long-term follow-up study that shows unexpectedly good rates of improvement for younger people who developed ME/CFS after infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever) – though the results are hardly spectacular.

Around 11 years on from getting sick, just over half of all ME/CFS patients were able to work part or full-time, though fatigue levels remained high:

The study was led by Dr. Morten Nyland and comes from the Neurology department of Haukeland University Hospital in Norway, site of the famed Rituximab pilot study. In fact two of the authors of this new paper were part of that pilot study. And although this wasn't a trial, patients were encouraged to use self-management (pacing/activity management), and the authors concluded that this probably contributed to the relatively good outcomes.

How the study worked (important)

An ideal study would take a bunch of patients and follow them at consistent time points, say the start of the illness, and then five and 10 years later. In this case, though, researchers made the most of pre-existing data to access a large group of patients who were followed up at very different times in their illness, an approach using two contact points that still yields invaluable results.

"Contact 1" was the first time the patient was seen by the specialist ME/CFS clinic at Haukeland University Hospital, any time between 1996 and 2006.

"Contact 2" was a follow-up questionnaire sent to all patiets in 2009, an average of 6.5 years later. There was huge variation in follow-up time between patients, for example at the second and final contact in 2009 one patient had been ill for 24 years and another only five years. The study had data at both contact points for 92 patients, making this one of the largest follow-up studies going.

At the initial contact, patients had been ill for an average of nearly five years, and again that hides a lot of variation. Half had been ill for 3.2 years or less, a quarter for under two years. The higher average was because some had been ill for a very long time. The patients were also relatively young (the average age was 24 years), reflecting the age profile of infectious mononucleosis, the 'kissing disease', which particularly affects young adults and teens.

Over half of all patients were employed at final contact

Pleasingly, the study used employment status as the clear-cut, objective primary outcome -- and arguably the ability to earn a living is the outcome that matters most to patients. The graph below shows a lot of improvement between first and second contact, which an average gap of six years, though the gap will vary a lot between patients.

Unemployment is in red while employment (full-time or part-time) or being a student is in green. Onset is when they got ill, Contact 1 is typically five years later, and Contact 2 typically another six years on.

Clearly things have improved for many patients, but the overall situation at Contact 2 remains a great deal worse than onset.

Note that half of those employed at Contact 2 were working full-time, compared with only 1 in 10 at Contact 1, so presumably there has been an increase in hours worked per person, as well as more people working.

Caution: It's possible that 11 years from onset (age 35 vs. age 24 at onset) some people would not be working anyway due to raising families so unemployment might not be zero even for a healthy group. And employment at onset wasn't split into full-time/part-time.

How patients said their overall health had changed

The study also asked patients how their overall health had changed since Contact 1 (their first visit to the clinic). Most patients said they had improved, 12% reported they had got worse.

Fatigue was also rated at both Contact 1 and Contact 2 using the Fatigue Severity Scale which gives an average score ranging from 1.0 (no fatigue) to 7.0 (maximum fatigue); any score of 5.0 or higher counts as severe fatigue. The average score at Contact 1 was 6.4, falling to 5.0 at Contact 2 -- so even after this improvement the group as a whole was right on the threshold of severe fatigue.

Different degrees of improvement

The study measured 'improvement' in several different ways. As well as change in employment status, they looked at self-rated improvement (including an option of 'recovered') and change in fatigue scores.

You can see that 'improvement' ranged from 70% reporting any improvement, to 32% moving into employment, and 13% who rated themselves as recovered.

Most people improved, even those who hadn't improved at Contact 1.

Another encouraging point was that of the 26 people who said they had already improved at Contact 1, 25 improved again by Contact 2. And of the 38 who reported they hadn't improved before, 25 (66%) improved by Contact 2.

Fatigue improved much less than employment status

One slightly strange finding, which the authors didn't comment on, is that average fatigue levels fall rather modestly compared with the percentage improving in employment status. While 32% of patients were able to start working, fatigue scores only fell from 6.4 to 5.0.

It seems likely that this in part is down to people getting back to work but still struggling, so that their level of fatigue doesn't improve as much as it might.

Interestingly, although 28% were working full-time only 13% rated themselves as 'recovered', which supports the view that some people are improving and choosing to work full-time despite not being completely well, and may still be struggling quite a lot.

What 'predicts' return to work/improvement over time? (not a lot)

Overall, this important new study shows that outcomes for younger people who develop ME/CFS after mono are not great, but are probably better than expected. Around half were in work 11 years after onset, though fatigue remains high for most.

What might be driving this improvement? The authors ran some fancy analysis to see what features (such as symptoms and age) predicted being in employment or an improved fatigue score at the final contact. It turned out that only lower joint pain at Contact 1 was associated with later employment, but the effect was small.

Similarly, low joint pain and depression at Contact 1, and better eduction, were predictors of less fatigue at Contact 2 -- but again the effect was small.

Surprisingly, length of illness was not an important predictor of employment or fatigue. Generally those with shorter illnesses are seen as having a better chance of recovery, but that doesn't appear to have been the case here.

It's possible that outcomes for ME/CFS after mono are better than after other triggers. I'll give the last word to the authors themselves, who suggest that both pacing/activity management and financial support through sickness benefits were likely to have played an important role to improvements:

"Self-management strategies, long-term sickness absence benefits providing a stable financial support, in addition to occupational interventions aimed at return to work were likely contributors to the generally positive, prolonged outcome."

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS researchPhoenix Rising thread discussing this paper, including the more detailed post that led to this blog.

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 c.(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. We’d also love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help in any way then please contact Mark through the Forums.

And don’t forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online! To find out more, visit Phoenix Rising’s Donate page by clicking the button below.

Continue reading the Original Blog Post

Last edited: