mango

Senior Member

- Messages

- 905

This transcript is also available as a downloadable PDF document on #MEAction's website:

Transcript: Solve ME/CFS Interviews Dr. Avi Nath

Thanks to the patients who transcribed this document

(Watch the recording on YouTube; Solve ME/CFS Initiative page with details)

Dr Zaher Nahle: Greetings! This is Zaher Nahle from the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, welcoming you to our second webinar of 2016. We are thrilled to have Dr Avi Nath from the NIH — a physician-scientist who is leading the intramural study on ME/CFS at the NIH — and this is an opportunity for the community to hear directly from Dr Nath.

Before giving the floor to Dr Nath, I would like to describe very briefly some of Avi Nath's credentials. Dr Nath received his medical degree from Christian Medical College in India, and then he completed the residency in neurology, followed by a fellowship in multiple sclerosis and neurovirology at the University of Texas, Houston.

He then did another fellowship in neuro-AIDS at the NINDS, which is the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH. Dr Nath held many faculty positions at the University of Manitoba and the University of Kentucky. He then became a professor at the Johns Hopkins University — Professor of Neurology as well as the Director of the Division of Neuroimmunology and Neurological Infections.

Dr Nath then moved to the NIH in 2011 to become the Clinical Director of NINDS, the Director of the Translational Neuroscience Center, as well as the Chief of the Section of Infections of the Nervous System. Dr Nath has research focuses on understanding the pathophysiology of retroviral infections and the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for these diseases.

For all these reasons, and for his leading role at the NIH intramural study on ME/CFS, we invited Dr Nath to talk to you today. Dr Nath, thank you, welcome, and the floor is yours.

Dr Avindra Nath: It's such a pleasure to have the opportunity to talk to all of you. And thank you very much for the invitation to join your forum. I'm absolutely thrilled and delighted to lead the intramural initiative on myalgic encephalomyelopathy and chronic fatigue syndrome, and I would like to take this opportunity to tell you a little bit about what we are planning to do. And then I look forward to answering some of your questions the best I can.

So, if you can see this slide, the purpose of putting this slide together here is that a number of things happened within the last year or so, because of which I've gotten involved. And one of them is that the Institute of Medicine put together this report that a lot of you may know. It's about 300 pages in size. And they discuss all the current literature on — related to — myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome and come up with their own terminology that they suggest. And they also discuss all the challenges that there are in diagnosis and the pathophysiology and where we currently stand, as far as management is concerned. It's actually a fairly well done piece. But about the same time there were other things that... [technical break]

So there was a paper published by the National Institutes of Health, which is a position paper on myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. And so they also took notice that there are very interesting aspects of the disease that need to be pursued further.

And so while all of this was happening I think there was a fair bit of community pressure as well, trying to figure out what needs to be done for chronic fatigue syndrome.

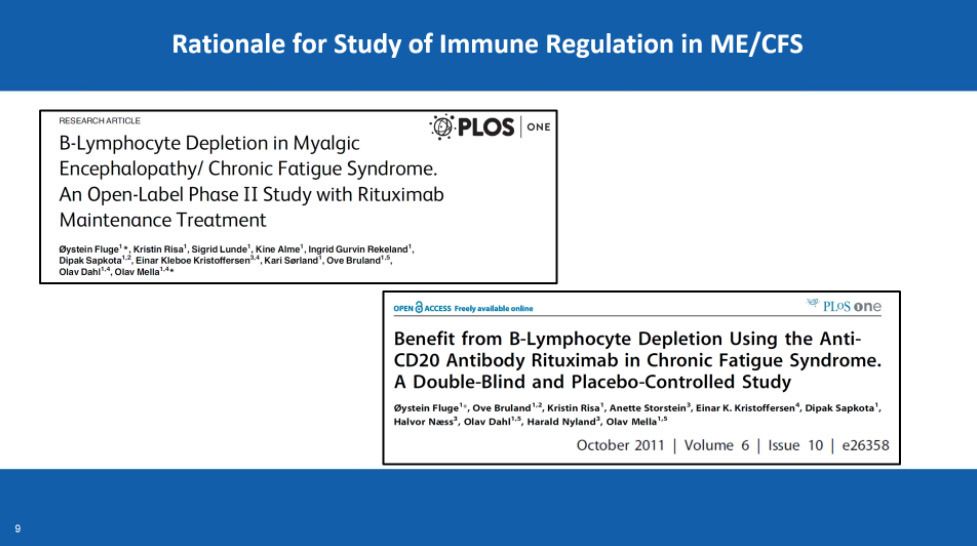

And there were two papers that came out also around that time from a group in Norway, claiming that they'd treated patients with an antibody that targets b-cells and there was some improvement in these patients. So one was an open-label study and the other was a double-blind study. So... and that suggested that maybe there is an immune component there, and if we can modulate it, maybe it can make a difference.

Now, there are many ways you can interpret these studies and when you look at things closely, you can always poke holes in these studies, but nonetheless it does provide some impetus for looking at the immune system and, as you know, there are several studies out there suggesting some kind of immune abnormality in these patients, although the findings have not been consistent.

But, looking at all that environment, it suggested that maybe bringing in experts who have devoted their careers to immunology may not be a bad idea, and trying to see how they interpret the literature and what they might suggest one should do to explore these possibilities.

OK, so let me tell you a little bit about the study. So when all of this was happening, Francis Collins, as the director of NIH, put together a panel of experts and met with all of us and discussed all the issues that were there related to the disease and he then turned to me and asked me if I would be willing to be the principal investigator of this study.

At that time it actually came to me as a surprise because I wasn't really expecting that. But, you know, I'd seen patients in my practice over many, many years and understand some aspects of the disease, particularly since I ran the Multiple sclerosis clinic for over two decades or more. I've seen a lot of patients there who have similar fatigue issues. Even in patients with Multiple sclerosis, actually it is the most disabling part of the disease. The physical abnormalities are really not as disabling as the fatigue part can be. And they do respond to immune-modulatory drugs, so... a reason to believe that there may be an immune abnormality underlying all of this, so for good reason, I guess, he turned to me.

And so I said that's fine, I'm willing to take a look at it and see if we can come up with something that would be an approach to studying this. So I looked at the literature myself, talked to a lot of people, and then we said that, OK, since my expertise is really in immunology and infections, what we really need to do is focus on that area, where our expertise lies.

So there is a subgroup of patients as you know, who have a very clear infectious process and then after that they get fatigued. And they just don't recover. Most of us do get some kind of infection or we will get fatigue, and then we get better after a while. Some people get infection, don't get fatigued. And then there's the subgroup that get fatigued and don't get better. And so that is the group that we thought we should target, because we could then try to see if the... how the infection and immunology interact with one another.

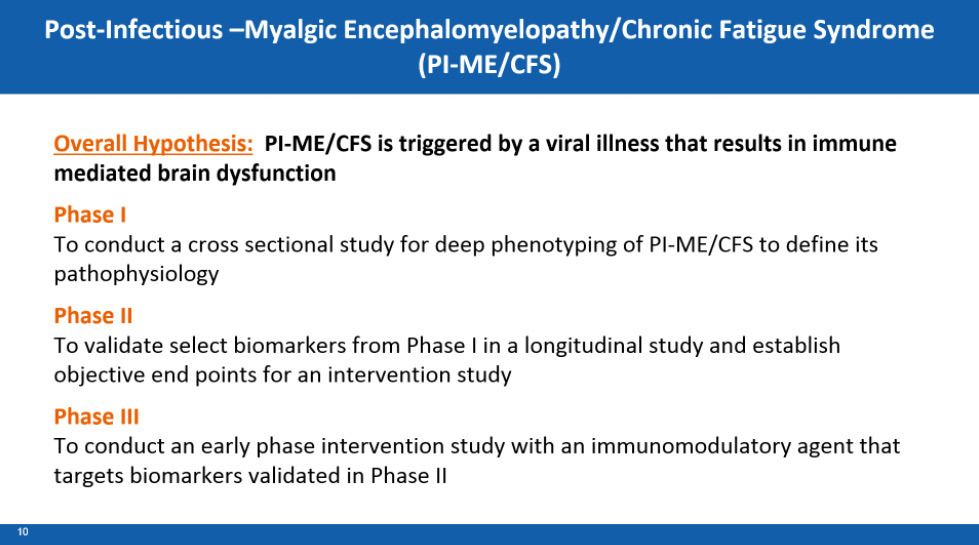

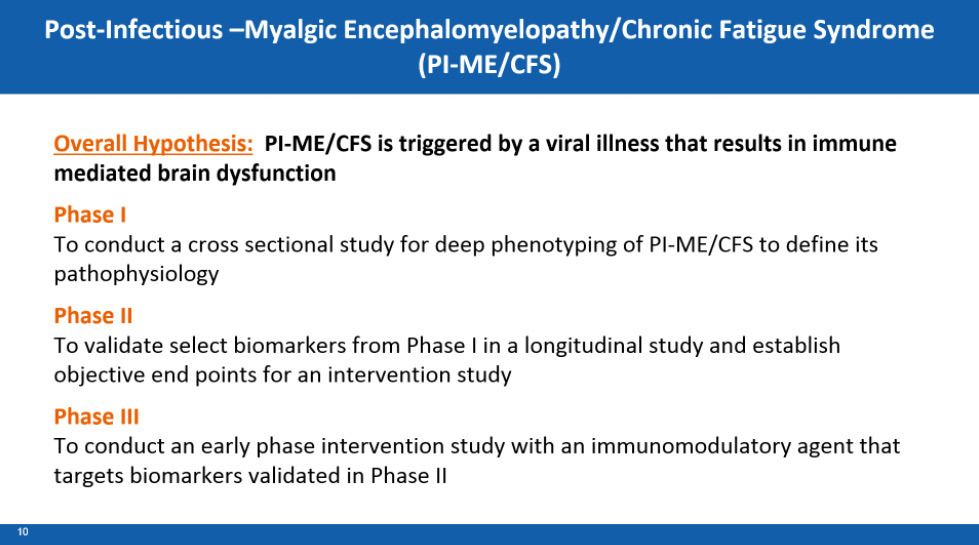

And so our overall hypothesis, then, for the study was that the syndrome is triggered by a viral illness that results in immune-mediated brain dysfunction. And so the brain part is key here because we think that a lot of these symptoms are probably triggered through the central nervous system. And so that brings in our expertise, right, so we have the virology, we have the immunology, and we have the neuroscience in here.

So we decided to do a three-phase study. And so that's what I presented to Dr Collins and the rest of the group, is that we really want to try and see if there was a way that we could get at the disease to be able to answer this specific question.

And so the first phase would be just a cross-sectional study so that we can do deep phenotyping. Phenotyping means that we try to characterize the clinical parameters of the patients. And the thing that you can do in the intramural program is the deep phenotyping. There's lots of stuff you can do that is very hard to do in other academic centers. And then I'll also define the pathophysiology associated with it.

So there are two ways of doing studies. You can do a lot of patients and do few things to them, or you can take a few patients and do a lot of things to them. And the intramural program is good at studying small sample sizes but studying them extensively. The extramural folks are really very good at multi-center studies and stuff whereby you can do very large numbers of patients.

So the first order usually should be to study a small number of patients, well-defined groups, and we look at them extensively, and that will allow you to define a set of parameters that you can then take to larger studies.

So after we conduct Phase One, hopefully find the handful of things that are worthy of pursuing further, then we would go to a Phase Two study. And so the Phase Two study would then validate the biomarkers in a longitudinal study. So now we can follow patients for a longer period of time and that will allow us to then establish endpoints if we can validate those in the longitudinal study. Then you can say that, OK, these are the things that seem to consistently be elevated or depressed or whatever it is. And if we now modulate one of those, will it really make a difference? So that's when you come to a Phase Three study.

And so the Phase Three study would then be an intervention study. And I've put down "immune modulatory agent" because that's what we're studying — the immune system — and so if you think that that is driving the disease in some way, then you want to see if you can modulate it or see if there's an effect or not. So that's in a summary as to what we were planning to do. And let me go to the next slide here.

So, I'm going into a little bit more detail about the Phase One part of our study. And the Phase One has two components. One is the patient and related study, and the second is a laboratory-based study.

So the clinical part of the study is that... is to define the clinical phenotypes. So that is basically getting a very detailed history and evaluation of all the systems that are involved. So we want to be able to understand each patient. Each patient is different and in any disease that you study there are certain things that are unique to each patient and there are certain things that are common within the disease. And you want to be able to capture both aspects of it.

So this means that we are going to have very detailed history and physical examination, neurological assessment, cognitive assessment, psychiatric evaluation, pain, headache, infectious disease and rheumatology — which really means auto-immune — and we'll look at the endocrine function, fatigue testing, exercise capacity, but we're also looking at the autonomic nervous system at the same time. So that should give us a decent understanding of the kinds of symptoms that the patients are experiencing.

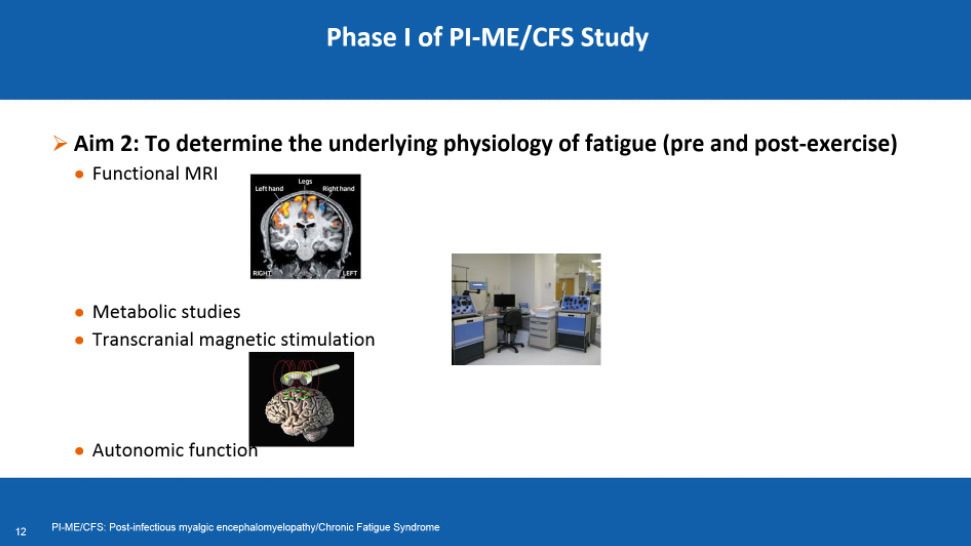

OK. And so once we've got the history and physical together then we're going to start investigating these patients. So the aim too will be to start looking at the brain in many different ways. So we will do a structural MRI scan: that means look at the structure of the brain. And then we do a functional MRI scan, which is, we give them particular tasks, either a motor task or a cognitive task, and look at oxygen uptake and bloodflow within the brain.

And so you give people a task and you will see that there are changes that occur in the brain. And so that tells you... and so you can put all of that together in a patient population and you can see if they are reacting normally or not. We can also do what is called a resting-state MRI: that means without giving them a task, you can actually see how the brain is reacting to oxygen and glucose uptake and that can be quite helpful. So we'll collect all that kind of information.

The intramural program also has a metabolic chamber so this is also quite unique. The patient is put there overnight and we collect a lot of information about their metabolism: how they utilize oxygen, glucose, kidney function, this, that and the other. So a lot of things you can get, like mitochondrial function. You can get an assessment of a lot of interesting things, and during the time when they are awake and asleep. So we will take advantage of that expertise as well.

And then we are going to do what is called transcranial magnetic stimulation. So now you can actually stimulate certain parts of the brain, and then record and see if the electrical impulses that are travelling through the brain are normal or not.

So these are all relatively new techniques that have become available in the very recent past and so... and we have access to all of those and we really have the world's experts. Some of them were actually developed — all these technologies were developed — within the intramural program, so the functional MRI scan, all the metabolic-chamber studies, transcranial magnetic stimulation... so we have the pioneers of all of these and I've asked all of them to participate in this study. So in that sense I'm very excited that we have the world's experts doing their piece.

And then we're going to study the autonomic function, as I mentioned earlier. And so... because a lot of patients do complain of autonomic symptoms. So we have also world-class experts in the autonomic nervous system and so those labs are willing to look at these patients as well. So they will do a variety of different things.

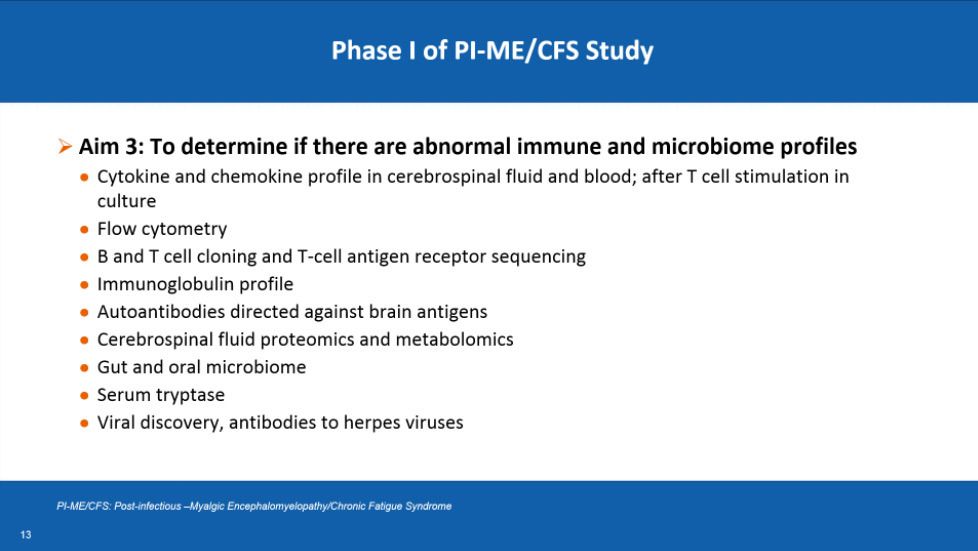

And then "aim three" is to look at all the immunology and the microbiology in these patients. And so what we will do is, we'll look at the spinal fluid and blood. We want to compare both of them. And so within my lab we have the ability to look at a lot of these different things.

And we have a centralized center of human immunology within the intramural program and they can look at about 1500 cytokines and chemokines and they also have the ability to do a lot of interesting functional studies. So I talked to them and they were very eager to help. So, depending on what we find in the cytokines, that will then tell us what kind of cellular function we need to study.

So initially we will just bank all of these things and then study them together once we have most of these patients enrolled. The other good thing about the intramural program is their ability to do flow cytometry. So these have to be done... while you can store CSF for studying t-cell function, cytokines and chemokines, flow cytometry has to be done on the day that you do the spinal tap. So you can't actually transport things from some other place.

And so we have the ability to do that on spinal fluid and some of our collaborators have published a lot in that field, so they are really very, very good at it. And they have a lot of data from other disease states too, so that's the other thing, that we have a wealth of information from other patient populations that we've been studying over the years. And so, using the same techniques, we can compare these against those patient populations and we can see how one disease is different from the other.

Then, depending on the kinds of findings we have from the first two, then we would.... Let's say it suggests that this is a b-cell mediated disorder, that's what we are finding there, then we will just clone out all the b-cells from these patients. And then we have the ability to study those in great detail, to try and understand what is normal or abnormal about their b-cells. Or we can do t-cells. Depending on whatever cell type we find, we can then go into more details there.

The good thing about the intramural program at NIH is that it has the largest and the best immunology program of any place in the world. So if there is a particular pattern that we start seeing I'm pretty sure I could find an expert here who could then take that further for me. So, even though I may not know on the outside where I could find anyone, I'm pretty confident that whatever we find, we can then explore further and then recruit experts for that purpose.

Another thing that my lab does really well is looking for autoantibodies, and so there've been some inconsistent reports in the literature about finding some kind of autoantibody here and there, and sometimes you can find a lot of false positives too, but my lab is very good at being able to characterize these things. And we do it in ways that are very different from other laboratories. So I'm eager to pursue that in my own lab.

And then, as I mentioned, we do a lot of proteomics, so we have one of the world's best mass [spectrometers] available in my lab. And we focus only on spinal fluid, so we have unique expertise in proteomics of the spinal fluid.

And then we will store specimens for looking at the microbiome and so I either will send that to Ian Lipkin or whoever is an expert in the field to look at those kinds of things.

And then there's a group at NIH who has studied serum tryptase. They're very keen to look at it. It's a simple test so I think that's perfectly fine, we'll send [inaudible] up to them.

And viral discovery and antibodies to herpes virus is, I think, all of those things... are things that we would like to pursue depending on what we find in the other tests.

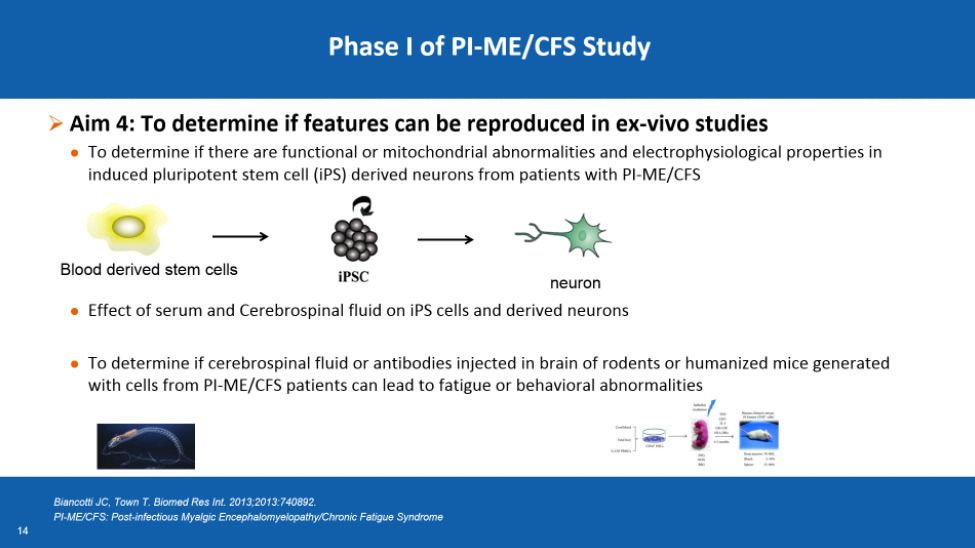

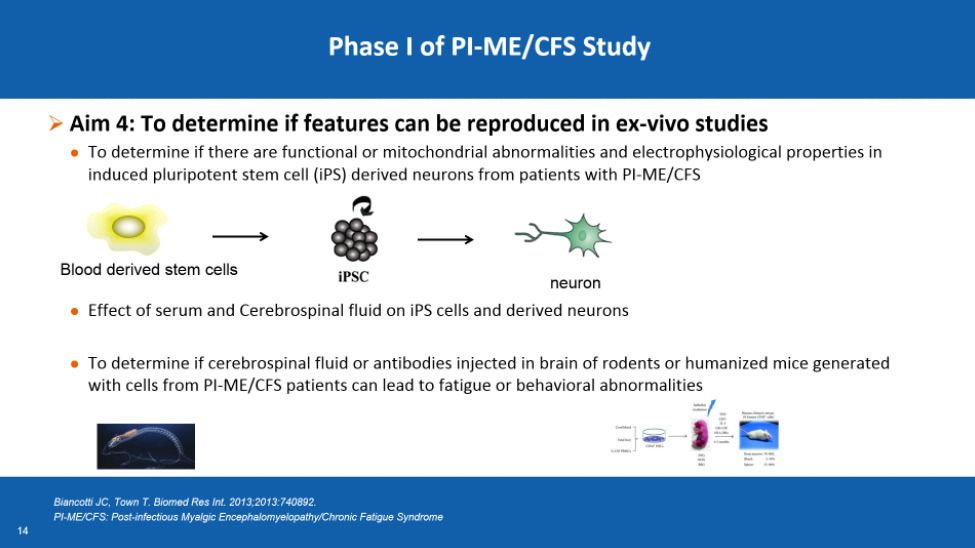

OK. So that is what you do with patient samples and patient characterization but then there is another aspect that I think is very critical and nobody has ever approached diseases that way, but that's the way I approach diseases now, for all the other diseases that I study in my laboratory.

What we do is, we now just take patients’ blood cells and we convert them into pluripotent stem cells and this is a technique that was also established in my lab. We were the first people to do it and I think other people are also now doing similar kinds of things.

So the problem in studying neurological diseases is that you cannot study a person's neuron in a dish. If you study dermatology, you can just take skin samples and study them, but brain cells cannot be studied in that manner. But the new technology now allows us to make neurons from blood cells from a single individual.

So, assuming that the abnormality is systemic — maybe there is a gene that's abnormal or whatever it might be — then we can actually make that individual's neurons. And so if we did that, and let's say there's an inherent mitochondrial dysfunction, then we can do all kinds of mitochondrial function studies on those neurons and we can determine whether there is an inherent abnormality or not.

So... and you can do electrophysiology on these neurons, so there are so many ways, sensitive kinds of testing you can do if you can culture neurons in a dish that you could never do in a human — an intact human being.

So that would be something that we would like to pursue in these patients. And when you've got these neurons in culture, now you can take the same individual patient whose neurons you made, you can take their blood samples and you can put them on the neuron and see if they cause any dysfunction to those neurons. Because of the... if the abnormality is a soluble factor, you might not actually find that in the neuron, it may actually be in the circulating blood or CSF. But now you have the opportunity to put it directly on the person's neuron and actually see what it does, so I think this is really exciting technology and these are techniques that we are very comfortable doing in our lab.

And then, lastly, what you want to do is reproduce the phenotype. You know, if there is a disease, the only way to prove that something is a cause of a disease is, you've got to reproduce the disease in some kind of a model. So, for example, you know HIV infection when we — "we" means the broad scientific community — had to show that HIV was the cause of AIDS, just isolating the virus wasn't good enough. You had to show that you can actually reproduce it.

So, ultimately it was done in chimps because animals couldn't be infected with HIV, and they showed that they came down with the exact same disease that humans have. And they were able to show that that was the cause of it, but it took many decades... no, it took many years, and lots and lots of laboratories to be able to do those kinds of experiments. But the same is true for most diseases. You have to be able to reproduce them in some manner.

And I think the technology today now is very different to what we had a few decades ago. And so now, what we can do is, we can take a mouse and we can humanize it. So we could take a person's cells and inject it into these mice whose bone marrow is impaired and they will actually take the human cells. And so if the cells have some abnormality in them, you'll be able to reproduce the clinical phenotype or the pathological phenotype if you have one, in these mice. So we plan on doing that and I think — and this will be part of the Phase One — and so I think if we're able to do that we could conclusively then demonstrate that... what the pathophysiology of the disease might be and try to home in to where the underlying abnormalities are.

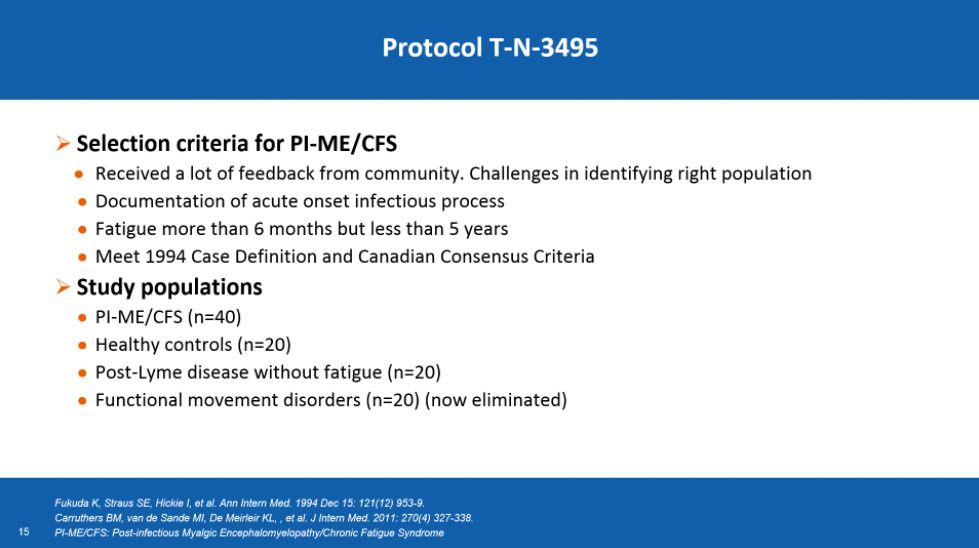

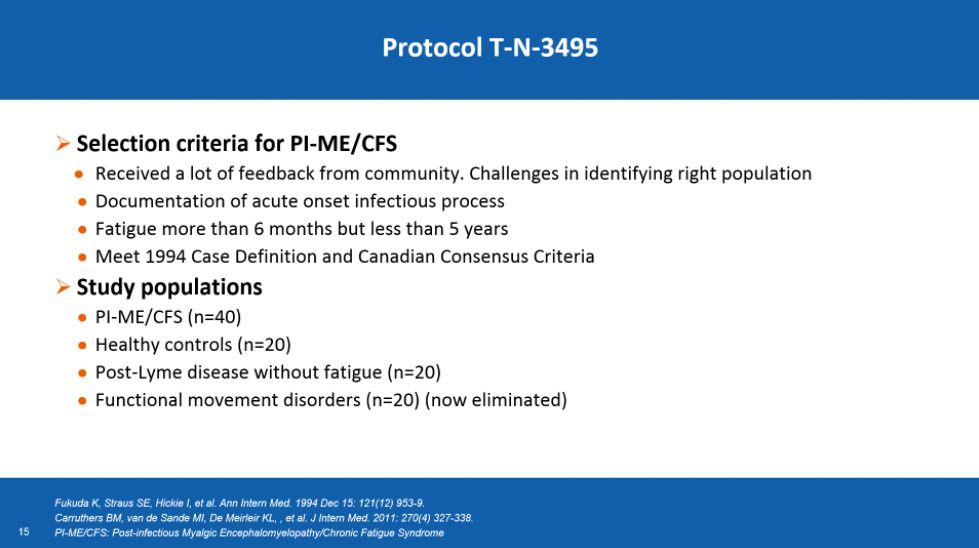

OK, let's go to the next slide here. OK, so who do we want to study? As I said earlier, you know, we want to study patients who have a clear infectious process and then have developed this syndrome. So, you know, we've received a lot criticism because we put down Reeves criteria on there, and I have to admit that, you know, I'm no expert in chronic fatigue syndrome. I didn't know how strongly people felt about poor Dr Reeves. I'd never met him and never knew anything about him.

But the reason we had put it over there is because — not that we want to follow the criteria, and I think that's where all the problems arose — we just wanted to use some kind of a quantification method and his questionnaires had all those kinds of quantification that we could do. So that's really all we wanted to get from there.

But the reality is that, really, the way we designed our study is we're going to bring patients in here and actually demonstrate that they will develop some post-exertional fatigue and without that, they're not even going to make it into our study. So actually it's very, very rigorous criteria, and I think one of the problems arises because you have only clinical criteria. So that's why all this controversy around — and this anxiety around — enrolling patients is an issue. And if you had a good biomarker, it would never be a problem.

We also realize that if you're going to use clinical criteria, not only for this disease but any other disease — and in neurology there are lots of them that way — they never have the perfect criteria and you're going to have some patients who probably don't have the disease, and you're going to have some kind of heterogeneity. But that doesn't actually bother me because as you study those patients you'll find outliers that don't fit into the rest of the group.

And so, depending on your sample size, you can actually add more patients or you can exclude them — the outliers — and re-analyze their data or sometimes the outliers can be actually very interesting. You can study them separately as well.

So there are ways of making adjustments to your study as you go along to try and define a population closer and closer and closer. So let's say I find, you know, there are ten patients out of the forty that are really clustering into a particular type of immune phenotype, then I'll try to understand what those are, and then try to bring in patients who keep matching that phenotype so I can correct right there for them.

So there are many ways of being able to handle it, so I'd like to alleviate people's anxiety that we might end up with wrong populations and all that kind of stuff. There are many ways of being able to handle those kinds of things and as neurologists we have lot of experience with those kinds of studies.

Then, there was also.... People don't want us to study the functional movement disorders. We have a nice cohort and Dr Hallett [?] has been studying these patients so they wanted to do that, but now for all of these reasons we have eliminated it. It actually simplifies our study, now we don't have too many more control populations. And our purpose is really not to develop a biomarker for chronic fatigue syndrome. That's not what our goal is. We really want to study the pathophysiology and identify the immune abnormalities in these patients. So we decided to eliminate it anyhow. I think that's it.

Then we have healthy controls. And the post-Lyme — again, we've got a really nice cohort of patients here at NIH and so these individuals have had an infectious process and then recovered from it. So you have an infection and you get worse, you have an infection and you get better. So we were going to enroll only those patients that got better, so we're not looking at this chronic Lyme or post-Lyme and all that other kind of stuff. We really are looking at individuals that had a clear infectious process and actually got better. So in a way they are... they should look like, everything like a healthy control, is what I would expect them to be. So anyway, that's what we have for our study population.

OK, so this is my last slide. So I put down a few statements here because I think these were the kinds of questions that were... we've gotten from the communities. I thought I should try to address some of these things the best I can. And then I'm happy to elaborate on them further or take other questions.

So the first is, I think, since there's so much interest in our study, I thought it probably is good for you to get to know a little bit of my own expertise and what you might expect from me as the PI of this study. So as I mentioned earlier, you know, I started my career in neurovirology, initially studying rubella virus then HIV, when HIV came along.

And now more recently I've gotten involved in studying some of the endogenous retroviruses that we think are involved in neurological diseases. And then some of the new viruses that have come out, like Ebola is one of them that we have been studying in Liberia, and now recently Zika virus, so our lab is focused on these two viruses as well.

So that's... So I come from a virology background and I am an expert both in clinical neuroinfectious disease, neuroimmunology, and as well as the basic science. So I have a full-fledged laboratory that studies these things and I'm proud to say that there aren't that many people in the world who can really do both clinical medicine and basic science, especially in the neuroimmunology or infectious disease realm.

And so we have special expertise that is available and we are glad to try and apply it to this disease to see if we can find something for these patients. So.... But also I should also mention that I'm not looking to become the world's expert in ME/CFS. That's not my goal. I just want to use my expertise to try and see if I can find something in this population, and then let the extramural world take it and run with it, and all the experts that are out there could then pursue it further. So I have a very focused goal. I want to try and answer that, and then move on to all the other things that I do.

And, I guess, the second question is quite obvious. I've tried to address that several times as to why I'm focusing on just that one group. Because I think that's where I can make a difference, or at least lend my expertise.

The study design, yes. So, I think one of the misconceptions out there was that once you design your study, then that's it. And if you find any kind of flaw, that's the... the whole world is going to come tumbling down or something. That's not the case. Any study that we design is always a process and evolution. You never really.... You might think you've got a really good design but you never really know until you start enrolling patients. You find out that, oops, I wanted to do all these tests but actually the patients can't even undergo this. Or maybe we didn't think of this: we need to actually add something just because we found something in some patients when we started. Or we need another control group because… for whatever reason.

So there are a lot of things that will evolve and I expect that to happen here as well. So just because we have designed something doesn't mean that's the end-all. I think we will, over a period of time, continue to modify the study as we see necessary, moving along.

Advantages and disadvantages of doing studies in the intramural program.... So, as I said, the advantage is that we really have world-class expertise available, technology available, that other institutions do not have. And the disadvantage is that we cannot do very large studies. You know, we've received emails: “Oh, you should be doing 80”, “You should be doing 100-and-some patients”, or whatever. We can't do that. We have a small hospital and we have only very limited beds. And we have lots of diseases that we study over here. And so we don't have the ability to do very large studies. It doesn't make much sense to do them here. Once you get to that stage, you do them extramural.

Team-members of the study.... So there are a lot of people who are on our.... Full-time people are only going to be a nurse and a coordinator, but everybody else who's on this study is actually lending their time towards this study. They are doing it in addition to whatever else they've been doing, so those responsibilities haven't gone away but they are taking on additional responsibilities for this study. So in all, there are close to about 150 or so investigators who are giving variable amounts of time towards this study here. There's lots of people involved.

And.... But I think what has happened is because media were just so... and it started scrutinizing the few names I put up over there, that a lot of people now come to me and say that, “You know what, I don't want you mentioning my name,” and then the other people said, “I don't want to have anything to do with it, I've got enough things that I'm doing”. And so that's become a bit of a challenge for me especially when there are very prominent scientists that I've approached that never will say no, but then they become reluctant to answer emails and so on, so you're going to kind of start getting a feeling that people feel that, do they really want their name out there on these kind of things?

So, I think people have to be a little bit careful as to how critical you become. You can end up....We're here to try and help. You can end up antagonizing all these people and they are, you know, busy doing other things. They're all.... There's no reason for them.... You can't force people to study your disease. People have to do it because they think it's important to study. So you've got to think that we're on the same team. And we want to really try and help, but we can't do that if the very people you want to help become antagonistic towards you.

So the other thing is there are a lot of comments we've received about biases and stuff like that. So if you have a large team and you have hundreds of people studying this disease you can't just go and do a litmus test on everyone and say that, “OK, well, you have a bias. We're not going to let you study this disease”. If you've got to eliminate all kinds of people, you’re never going to be able to study anything. Rather, you do as you're designing your study whereby you don't have to worry about people's biases. I think that's the way to do these things.

If I, you know.... I‘ve made my career studying AIDS. If I said “OK, I'm going to do a litmus test on everybody who study AIDS in this country and if you have any kind of adverse views about gay people and this, that and the other, you know, you shouldn't be studying this”. And we'll never have made any kind of advances. I think we made lots of advances and we know that people have all kinds of biases and we shouldn't worry about those kind of things. What we really need to do is focus on the disease and on the patients and try to get to the bottom of the disease. And that's what my goal really is.

And then, communication with the community: I think that's important. So we're happy to communicate. And so our offices are also trying their best to communicate with people that they can. I personally answered emails for people as well. You also have to realize we are doing a lot of other daytime job, a lot of other things too, so we can't.... If you send me an email that's, you know, three pages long I'll not even have the time to read the thing. So they have to be short and I'll give out short answers. You know, I never learned to type so I’ve got to type with one finger here, and so there will be short answers but I try the best that I can in order to answer all of these things. You know, we don't have a 9-to-5 job here, it's a 24-hour job, even though we work for the government, and so we do the best we can and hopefully you will see that we've been responsive.

The other way that we try to communicate with the community is by putting up a webpage. A lot of the questions that we see are repetitious. They all seem very similar in many, many ways and so we thought the best thing to do is just to put up those questions there with appropriate answers and hopefully that is beneficial to everyone. And if there.... And then we modify it from time to time, depending on new questions that come up.

So, then, lastly is the timeline of the study. So the study, as you know, has been IRB approved. We had to go and modify it to take out one control group so when you take out another control group it has to go through scientific review and through IRB all over again. So now it's gone through scientific review and is sitting back in the IRB. So we are awaiting IRB approval there. And now we are also trying to hire a nurse and a coordinator, and those positions are being advertised.

So my hope is that by the summer we'll start enrolling. But when we start enrolling we're going to start with the normal volunteers first, because that's where you're going to iron out all your kinks in the system. And they are doing so many different tests and making sure they are all coordinated, and one has to be done before the other and so on and so forth. So you want to start with healthy volunteers and make sure you've got it right and then we'll start enrolling patients with ME/CFS.

OK, so I'll stop here. And I'm happy to take any questions that anybody has.

Dr Nahle: Thank you Dr Nath, this was very informative. We received so many questions and I will go directly to them. I have some on my own but I'll leave them until the end. Again, we will not be able to finish all the questions, so thank you for agreeing to answer them at a later time, which then will be posted on our website.

Just a brief comment on the Reeves criteria and as you explained that... how you approach them. I think the community was shocked at the beginning of the release of this protocol because it has been an enormous amount of study and expertise on this in the last ten years, so they felt, including us, that not enough reach-out has been done by the NIH to learn from the experts who have been studying this extensively, and thank you for your explanation to this.

Many of the questions you have touched on already, but let me go to this one directly: “Would you agree that scientists/doctors who select patients representative of an illness group have the power to influence the outcomes of studies into that illness?” That's a two part question, so this is the Part One. And then, “What steps are you taking to make sure the researchers controlling the patients’ select process are not letting their personal beliefs about ME/CFS skew the results of your studies into ME/CFS?” You touched on that. Can you elaborate a little bit, Dr Nath?

Dr Nath: You know, I tried to address that already. I anticipated this question, it has come to us so many different times. It’s that you're not going to eliminate everybody's biases, OK, you can't know how people are thinking in their brain, right? So, what you want to do is design your study that it makes that irrelevant. And so, what we've done is, we've.... The patients we are going to get are going to come from experts in the field who are already studying these patients, so from all the CDC clinics that are out there. And they will send us the patients. We will look at them, make sure they meet all our criteria and then enroll them. So that way, you know, the experts are providing us the patient population.

Dr Nahle: Thank you, Dr Nath, for this candor. If I may follow up on this, I think we receive similar questions like that, especially on the bias. I believe the questioner was meaning: here on this study team, we know that members of the team have expressed in the past opinions on somatizations and things like that, so I believe this probably was the crux of the question. Not about the population itself but I appreciate your candor on this and... but you know, if we can get that clarified a little bit, just briefly.

Dr Nath: Yeah, so that's what I said, I can't... Let's say I can force people, say, “You know what? Don't say there's any somatization and change your views on it,” or I could eliminate the team and try to hire new people who say that, “No, no, I don't have any bias”. How do I know they have or they don't have? I don't know what they think in their own brain. So, I know what my role is. I know.... I'm a neuroimmunologist: I don't know anything about psychology. That's not my area of expertise. Somatization, I know nothing about. So that's not what I'm interested in.

I'm really interested in getting into the immunology. The way I’ve designed my study is, that's the only question I'm going to answer. I mean, I've got too many other things going on, I don't have time to be doing all this psychological stuff or play psychological games with people. I want to design a study that's going to be... that would not have any influence or any bias. So even if a person has all kinds of biases I should be able to design a study that is not influenced by that. And I think by studying the way I've outlined over here, I think we can do a study that should not have those kinds of concerns any longer.

Dr Nahle: Thank you. Thank you for your answer. So, moving on to other questions. We have, as I said, many and we will probably take a few more. This one, we received three questions like that, it's a technical question. I have a question about, “I understand that they will be — “they” you — will be doing a two-day maximum exercise testing. But will they do the full Stevens protocol, i.e. measure the CPET-values and see if they can validate the findings of the Stevens, VanNess etc., Keller studies?

Dr Nath: You know I'm not the world's expert on these kinds of.... My major goal here is to study neuroimmunology. And so every single aspect of it is not my goal. I just want to be able to fatigue patients and see that if before and after fatigue, is there a change in the immune profile? OK. So, that's really my goal. And so the test that we have in order to fatigue patients is going to be different. Some patients are going to get fatigued very easily, some are going to take a long [inaudible] to do it, but once they get fatigued we're going to be able to study their immune profile before and after. And so that's really my goal.

Dr Nahle: And would these experts be consulted? Are you open to these kinds of overtures?

Dr Nath: Yeah, so let me just address that issue too. You know, I have received names of hundreds of experts that I should be talking to. They say, “Well, have you talked to this person? Did you talk with that person?” I can't talk to everybody in the world who claims they are an expert. That isn’t going to solve any of our problems, you know, and I'm not trying to become an expert in this field. And I'm not changing my career at all.

So what we've done is, I've started a seminar series. And so I'm going to bring in people who claim expertise in the field, and let them come in and give us a presentation. They spend the day with us, and they get to meet the entire team and I think that will be a much more fruitful interaction than me getting on the phone and talking to everybody: “Oh yeah, so what advice can you give me?” And there will be conflicting views and that kind of stuff. I won't be able to sort out one from the other. So I think that this approach of bringing in people here and starting a seminar series might be one way of being able to handle it.

Dr Nahle: OK, thank you. This question just came in. “Have you spoken to—“ Again, this is along the same line, this is along the Rituximab studies that you mentioned in your presentations, they are asking. “Have you spoken to Dr Fluge or Mella in Norway regarding their work?” I guess we already answered that.

Dr Nath: Let me just say, anybody who publishes a paper and they expect me to go call them and talk to them? I, you know, I've seen their study, I know what the pros and cons of their study is. If I can find the same abnormalities, I'm going to do a much, much more extensive study than those guys ever did. And I'll be able to know whether I can believe their findings or not. And so.... But sure, and at some point in time we'll invite them, we'd like for them to present their data. They might have other things that they haven't published. We'd love to be able to see those kinds of things.

But every time somebody publishes a paper I'm not going to go start calling them up and try and talk to them. And that's not the way I've ever done science and I don't plan on doing that. It just doesn't make much sense.

Dr Nahle: OK, thank you. “Do you have plans to test for muscarinic and adrenergic autoantibodies already found in parts in ME/CFS?” And again, I'm posing the questions as I'm reading them.

Dr Nath: OK, so, you know I said, I don't want to look at a biased approach. I'm looking for autoantibodies, there are lots of autoantibodies people have published on, they can reproduce it, some they cannot. I have a very unique way of looking at autoantibodies and we've found autoantibodies that every lab in the world has failed to identify them. So we have a really unique way of looking at autoantibodies to the brain. We have brain homogenates that we produce, various stages of cell differentiation, and we have it from normal tissue, from pathological tissues, all kinds of stuff.

So we have... and we use mass spectroscopy for identification of the antigens. So I'm pretty certain that if there is an autoantibody to anything in the brain, we'll find it. And we'll be able to define the subgroup that actually has any kind of autoantibodies. So that's going to be our approach.

Dr Nahle: Great, thank you. Another question. “How often will the researchers in the intramural study be analyzing their samples?”

Dr Nath: I don't understand.

Dr Nahle: So how many, how many.... This is the question: “How often will the researchers in the intramural study be analyzing...?” Their question: “Will there be repetition and maybe different time points?” I think that's what the questioner is asking.

Dr Nath: Yes, I think we are collecting some samples we are collecting from two time points, for example spinal fluid. You cannot do multiple spinal taps on people, so largely that will be a single time point although some patients may be willing to undergo it a second time. But for most things we want to do it before and after exercise so that will be two samples, except for some invasive [inaudible].

Dr Nahle: OK, great. There is a timeline question: “How often for Phase One completion?” You eloquently explained the phases, how.... What's your expectation for that?

Dr Nath: Timeframe? Oh, OK. So the thing is, when we bring in a patient, we're studying them very extensively. They are here for almost a week. And so we have 40 patients and another 40 controls. 80 patients, so that could take us a good two years to enroll the study. And that's assuming.... It could take longer because sometimes patients cancel or whatever happens and so I think minimum it will take us two years.

Dr Nahle: And, then, this probably is a related question on patient participation as the result of the studies will be rolled out: “Will the study incorporate patient representatives into planning, conduct and data analysis of the study?” What's your opinion on that?

Dr Nath: I didn't understand that. Say that again?

Dr Nahle: Will this study incorporate patient representatives, patient representation.

Dr Nath: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah. So I'm very eager to do that. The thing is that as I've been talking to people, one of the questions goes, “Who's the patient representative and how many are you going to get? What their role should be?” So, turns out to be much more complicated than I originally imagined. So the extramural folks are much more cognizant of these kinds of things. I think they already have approached people or are approaching people and putting together a panel, and so as they do that we'll be delighted to use that same panel for our study. And so.... But I am all for communication with the patients and patient representatives. And I think that feedback is important and I value that very much. But I... the mechanism... I'm not a hundred percent sure I know exactly how best to do it.

Dr Nahle: OK, thank you. Thank you. You know, we have so many, again, we have so many questions, and I appreciate you agreeing to answering those off-webinar. We came to the conclusion of this webinar. Again, this was informative, very informative. Thank you for doing this. Many of the remaining questions are technical; some talk about the planning and more in-depth understanding. Every question we receive is very important to us. That's why we will follow up with you, Dr Nath. Thank you so much, and thank you everybody for participating in this webinar. Please stay tuned for our next one, and good day to you.

Dr Nath: All right, thank you.

Dr Nahle: Thank you.

Transcript: Solve ME/CFS Interviews Dr. Avi Nath

Thanks to the patients who transcribed this document

(Watch the recording on YouTube; Solve ME/CFS Initiative page with details)

Dr Zaher Nahle: Greetings! This is Zaher Nahle from the Solve ME/CFS Initiative, welcoming you to our second webinar of 2016. We are thrilled to have Dr Avi Nath from the NIH — a physician-scientist who is leading the intramural study on ME/CFS at the NIH — and this is an opportunity for the community to hear directly from Dr Nath.

Before giving the floor to Dr Nath, I would like to describe very briefly some of Avi Nath's credentials. Dr Nath received his medical degree from Christian Medical College in India, and then he completed the residency in neurology, followed by a fellowship in multiple sclerosis and neurovirology at the University of Texas, Houston.

He then did another fellowship in neuro-AIDS at the NINDS, which is the National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the NIH. Dr Nath held many faculty positions at the University of Manitoba and the University of Kentucky. He then became a professor at the Johns Hopkins University — Professor of Neurology as well as the Director of the Division of Neuroimmunology and Neurological Infections.

Dr Nath then moved to the NIH in 2011 to become the Clinical Director of NINDS, the Director of the Translational Neuroscience Center, as well as the Chief of the Section of Infections of the Nervous System. Dr Nath has research focuses on understanding the pathophysiology of retroviral infections and the development of new diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for these diseases.

For all these reasons, and for his leading role at the NIH intramural study on ME/CFS, we invited Dr Nath to talk to you today. Dr Nath, thank you, welcome, and the floor is yours.

Dr Avindra Nath: It's such a pleasure to have the opportunity to talk to all of you. And thank you very much for the invitation to join your forum. I'm absolutely thrilled and delighted to lead the intramural initiative on myalgic encephalomyelopathy and chronic fatigue syndrome, and I would like to take this opportunity to tell you a little bit about what we are planning to do. And then I look forward to answering some of your questions the best I can.

So, if you can see this slide, the purpose of putting this slide together here is that a number of things happened within the last year or so, because of which I've gotten involved. And one of them is that the Institute of Medicine put together this report that a lot of you may know. It's about 300 pages in size. And they discuss all the current literature on — related to — myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome and come up with their own terminology that they suggest. And they also discuss all the challenges that there are in diagnosis and the pathophysiology and where we currently stand, as far as management is concerned. It's actually a fairly well done piece. But about the same time there were other things that... [technical break]

So there was a paper published by the National Institutes of Health, which is a position paper on myalgic encephalomyelitis and chronic fatigue syndrome. And so they also took notice that there are very interesting aspects of the disease that need to be pursued further.

And so while all of this was happening I think there was a fair bit of community pressure as well, trying to figure out what needs to be done for chronic fatigue syndrome.

And there were two papers that came out also around that time from a group in Norway, claiming that they'd treated patients with an antibody that targets b-cells and there was some improvement in these patients. So one was an open-label study and the other was a double-blind study. So... and that suggested that maybe there is an immune component there, and if we can modulate it, maybe it can make a difference.

Now, there are many ways you can interpret these studies and when you look at things closely, you can always poke holes in these studies, but nonetheless it does provide some impetus for looking at the immune system and, as you know, there are several studies out there suggesting some kind of immune abnormality in these patients, although the findings have not been consistent.

But, looking at all that environment, it suggested that maybe bringing in experts who have devoted their careers to immunology may not be a bad idea, and trying to see how they interpret the literature and what they might suggest one should do to explore these possibilities.

OK, so let me tell you a little bit about the study. So when all of this was happening, Francis Collins, as the director of NIH, put together a panel of experts and met with all of us and discussed all the issues that were there related to the disease and he then turned to me and asked me if I would be willing to be the principal investigator of this study.

At that time it actually came to me as a surprise because I wasn't really expecting that. But, you know, I'd seen patients in my practice over many, many years and understand some aspects of the disease, particularly since I ran the Multiple sclerosis clinic for over two decades or more. I've seen a lot of patients there who have similar fatigue issues. Even in patients with Multiple sclerosis, actually it is the most disabling part of the disease. The physical abnormalities are really not as disabling as the fatigue part can be. And they do respond to immune-modulatory drugs, so... a reason to believe that there may be an immune abnormality underlying all of this, so for good reason, I guess, he turned to me.

And so I said that's fine, I'm willing to take a look at it and see if we can come up with something that would be an approach to studying this. So I looked at the literature myself, talked to a lot of people, and then we said that, OK, since my expertise is really in immunology and infections, what we really need to do is focus on that area, where our expertise lies.

So there is a subgroup of patients as you know, who have a very clear infectious process and then after that they get fatigued. And they just don't recover. Most of us do get some kind of infection or we will get fatigue, and then we get better after a while. Some people get infection, don't get fatigued. And then there's the subgroup that get fatigued and don't get better. And so that is the group that we thought we should target, because we could then try to see if the... how the infection and immunology interact with one another.

And so our overall hypothesis, then, for the study was that the syndrome is triggered by a viral illness that results in immune-mediated brain dysfunction. And so the brain part is key here because we think that a lot of these symptoms are probably triggered through the central nervous system. And so that brings in our expertise, right, so we have the virology, we have the immunology, and we have the neuroscience in here.

So we decided to do a three-phase study. And so that's what I presented to Dr Collins and the rest of the group, is that we really want to try and see if there was a way that we could get at the disease to be able to answer this specific question.

And so the first phase would be just a cross-sectional study so that we can do deep phenotyping. Phenotyping means that we try to characterize the clinical parameters of the patients. And the thing that you can do in the intramural program is the deep phenotyping. There's lots of stuff you can do that is very hard to do in other academic centers. And then I'll also define the pathophysiology associated with it.

So there are two ways of doing studies. You can do a lot of patients and do few things to them, or you can take a few patients and do a lot of things to them. And the intramural program is good at studying small sample sizes but studying them extensively. The extramural folks are really very good at multi-center studies and stuff whereby you can do very large numbers of patients.

So the first order usually should be to study a small number of patients, well-defined groups, and we look at them extensively, and that will allow you to define a set of parameters that you can then take to larger studies.

So after we conduct Phase One, hopefully find the handful of things that are worthy of pursuing further, then we would go to a Phase Two study. And so the Phase Two study would then validate the biomarkers in a longitudinal study. So now we can follow patients for a longer period of time and that will allow us to then establish endpoints if we can validate those in the longitudinal study. Then you can say that, OK, these are the things that seem to consistently be elevated or depressed or whatever it is. And if we now modulate one of those, will it really make a difference? So that's when you come to a Phase Three study.

And so the Phase Three study would then be an intervention study. And I've put down "immune modulatory agent" because that's what we're studying — the immune system — and so if you think that that is driving the disease in some way, then you want to see if you can modulate it or see if there's an effect or not. So that's in a summary as to what we were planning to do. And let me go to the next slide here.

So, I'm going into a little bit more detail about the Phase One part of our study. And the Phase One has two components. One is the patient and related study, and the second is a laboratory-based study.

So the clinical part of the study is that... is to define the clinical phenotypes. So that is basically getting a very detailed history and evaluation of all the systems that are involved. So we want to be able to understand each patient. Each patient is different and in any disease that you study there are certain things that are unique to each patient and there are certain things that are common within the disease. And you want to be able to capture both aspects of it.

So this means that we are going to have very detailed history and physical examination, neurological assessment, cognitive assessment, psychiatric evaluation, pain, headache, infectious disease and rheumatology — which really means auto-immune — and we'll look at the endocrine function, fatigue testing, exercise capacity, but we're also looking at the autonomic nervous system at the same time. So that should give us a decent understanding of the kinds of symptoms that the patients are experiencing.

OK. And so once we've got the history and physical together then we're going to start investigating these patients. So the aim too will be to start looking at the brain in many different ways. So we will do a structural MRI scan: that means look at the structure of the brain. And then we do a functional MRI scan, which is, we give them particular tasks, either a motor task or a cognitive task, and look at oxygen uptake and bloodflow within the brain.

And so you give people a task and you will see that there are changes that occur in the brain. And so that tells you... and so you can put all of that together in a patient population and you can see if they are reacting normally or not. We can also do what is called a resting-state MRI: that means without giving them a task, you can actually see how the brain is reacting to oxygen and glucose uptake and that can be quite helpful. So we'll collect all that kind of information.

The intramural program also has a metabolic chamber so this is also quite unique. The patient is put there overnight and we collect a lot of information about their metabolism: how they utilize oxygen, glucose, kidney function, this, that and the other. So a lot of things you can get, like mitochondrial function. You can get an assessment of a lot of interesting things, and during the time when they are awake and asleep. So we will take advantage of that expertise as well.

And then we are going to do what is called transcranial magnetic stimulation. So now you can actually stimulate certain parts of the brain, and then record and see if the electrical impulses that are travelling through the brain are normal or not.

So these are all relatively new techniques that have become available in the very recent past and so... and we have access to all of those and we really have the world's experts. Some of them were actually developed — all these technologies were developed — within the intramural program, so the functional MRI scan, all the metabolic-chamber studies, transcranial magnetic stimulation... so we have the pioneers of all of these and I've asked all of them to participate in this study. So in that sense I'm very excited that we have the world's experts doing their piece.

And then we're going to study the autonomic function, as I mentioned earlier. And so... because a lot of patients do complain of autonomic symptoms. So we have also world-class experts in the autonomic nervous system and so those labs are willing to look at these patients as well. So they will do a variety of different things.

And then "aim three" is to look at all the immunology and the microbiology in these patients. And so what we will do is, we'll look at the spinal fluid and blood. We want to compare both of them. And so within my lab we have the ability to look at a lot of these different things.

And we have a centralized center of human immunology within the intramural program and they can look at about 1500 cytokines and chemokines and they also have the ability to do a lot of interesting functional studies. So I talked to them and they were very eager to help. So, depending on what we find in the cytokines, that will then tell us what kind of cellular function we need to study.

So initially we will just bank all of these things and then study them together once we have most of these patients enrolled. The other good thing about the intramural program is their ability to do flow cytometry. So these have to be done... while you can store CSF for studying t-cell function, cytokines and chemokines, flow cytometry has to be done on the day that you do the spinal tap. So you can't actually transport things from some other place.

And so we have the ability to do that on spinal fluid and some of our collaborators have published a lot in that field, so they are really very, very good at it. And they have a lot of data from other disease states too, so that's the other thing, that we have a wealth of information from other patient populations that we've been studying over the years. And so, using the same techniques, we can compare these against those patient populations and we can see how one disease is different from the other.

Then, depending on the kinds of findings we have from the first two, then we would.... Let's say it suggests that this is a b-cell mediated disorder, that's what we are finding there, then we will just clone out all the b-cells from these patients. And then we have the ability to study those in great detail, to try and understand what is normal or abnormal about their b-cells. Or we can do t-cells. Depending on whatever cell type we find, we can then go into more details there.

The good thing about the intramural program at NIH is that it has the largest and the best immunology program of any place in the world. So if there is a particular pattern that we start seeing I'm pretty sure I could find an expert here who could then take that further for me. So, even though I may not know on the outside where I could find anyone, I'm pretty confident that whatever we find, we can then explore further and then recruit experts for that purpose.

Another thing that my lab does really well is looking for autoantibodies, and so there've been some inconsistent reports in the literature about finding some kind of autoantibody here and there, and sometimes you can find a lot of false positives too, but my lab is very good at being able to characterize these things. And we do it in ways that are very different from other laboratories. So I'm eager to pursue that in my own lab.

And then, as I mentioned, we do a lot of proteomics, so we have one of the world's best mass [spectrometers] available in my lab. And we focus only on spinal fluid, so we have unique expertise in proteomics of the spinal fluid.

And then we will store specimens for looking at the microbiome and so I either will send that to Ian Lipkin or whoever is an expert in the field to look at those kinds of things.

And then there's a group at NIH who has studied serum tryptase. They're very keen to look at it. It's a simple test so I think that's perfectly fine, we'll send [inaudible] up to them.

And viral discovery and antibodies to herpes virus is, I think, all of those things... are things that we would like to pursue depending on what we find in the other tests.

OK. So that is what you do with patient samples and patient characterization but then there is another aspect that I think is very critical and nobody has ever approached diseases that way, but that's the way I approach diseases now, for all the other diseases that I study in my laboratory.

What we do is, we now just take patients’ blood cells and we convert them into pluripotent stem cells and this is a technique that was also established in my lab. We were the first people to do it and I think other people are also now doing similar kinds of things.

So the problem in studying neurological diseases is that you cannot study a person's neuron in a dish. If you study dermatology, you can just take skin samples and study them, but brain cells cannot be studied in that manner. But the new technology now allows us to make neurons from blood cells from a single individual.

So, assuming that the abnormality is systemic — maybe there is a gene that's abnormal or whatever it might be — then we can actually make that individual's neurons. And so if we did that, and let's say there's an inherent mitochondrial dysfunction, then we can do all kinds of mitochondrial function studies on those neurons and we can determine whether there is an inherent abnormality or not.

So... and you can do electrophysiology on these neurons, so there are so many ways, sensitive kinds of testing you can do if you can culture neurons in a dish that you could never do in a human — an intact human being.

So that would be something that we would like to pursue in these patients. And when you've got these neurons in culture, now you can take the same individual patient whose neurons you made, you can take their blood samples and you can put them on the neuron and see if they cause any dysfunction to those neurons. Because of the... if the abnormality is a soluble factor, you might not actually find that in the neuron, it may actually be in the circulating blood or CSF. But now you have the opportunity to put it directly on the person's neuron and actually see what it does, so I think this is really exciting technology and these are techniques that we are very comfortable doing in our lab.

And then, lastly, what you want to do is reproduce the phenotype. You know, if there is a disease, the only way to prove that something is a cause of a disease is, you've got to reproduce the disease in some kind of a model. So, for example, you know HIV infection when we — "we" means the broad scientific community — had to show that HIV was the cause of AIDS, just isolating the virus wasn't good enough. You had to show that you can actually reproduce it.

So, ultimately it was done in chimps because animals couldn't be infected with HIV, and they showed that they came down with the exact same disease that humans have. And they were able to show that that was the cause of it, but it took many decades... no, it took many years, and lots and lots of laboratories to be able to do those kinds of experiments. But the same is true for most diseases. You have to be able to reproduce them in some manner.

And I think the technology today now is very different to what we had a few decades ago. And so now, what we can do is, we can take a mouse and we can humanize it. So we could take a person's cells and inject it into these mice whose bone marrow is impaired and they will actually take the human cells. And so if the cells have some abnormality in them, you'll be able to reproduce the clinical phenotype or the pathological phenotype if you have one, in these mice. So we plan on doing that and I think — and this will be part of the Phase One — and so I think if we're able to do that we could conclusively then demonstrate that... what the pathophysiology of the disease might be and try to home in to where the underlying abnormalities are.

OK, let's go to the next slide here. OK, so who do we want to study? As I said earlier, you know, we want to study patients who have a clear infectious process and then have developed this syndrome. So, you know, we've received a lot criticism because we put down Reeves criteria on there, and I have to admit that, you know, I'm no expert in chronic fatigue syndrome. I didn't know how strongly people felt about poor Dr Reeves. I'd never met him and never knew anything about him.

But the reason we had put it over there is because — not that we want to follow the criteria, and I think that's where all the problems arose — we just wanted to use some kind of a quantification method and his questionnaires had all those kinds of quantification that we could do. So that's really all we wanted to get from there.

But the reality is that, really, the way we designed our study is we're going to bring patients in here and actually demonstrate that they will develop some post-exertional fatigue and without that, they're not even going to make it into our study. So actually it's very, very rigorous criteria, and I think one of the problems arises because you have only clinical criteria. So that's why all this controversy around — and this anxiety around — enrolling patients is an issue. And if you had a good biomarker, it would never be a problem.

We also realize that if you're going to use clinical criteria, not only for this disease but any other disease — and in neurology there are lots of them that way — they never have the perfect criteria and you're going to have some patients who probably don't have the disease, and you're going to have some kind of heterogeneity. But that doesn't actually bother me because as you study those patients you'll find outliers that don't fit into the rest of the group.

And so, depending on your sample size, you can actually add more patients or you can exclude them — the outliers — and re-analyze their data or sometimes the outliers can be actually very interesting. You can study them separately as well.

So there are ways of making adjustments to your study as you go along to try and define a population closer and closer and closer. So let's say I find, you know, there are ten patients out of the forty that are really clustering into a particular type of immune phenotype, then I'll try to understand what those are, and then try to bring in patients who keep matching that phenotype so I can correct right there for them.

So there are many ways of being able to handle it, so I'd like to alleviate people's anxiety that we might end up with wrong populations and all that kind of stuff. There are many ways of being able to handle those kinds of things and as neurologists we have lot of experience with those kinds of studies.

Then, there was also.... People don't want us to study the functional movement disorders. We have a nice cohort and Dr Hallett [?] has been studying these patients so they wanted to do that, but now for all of these reasons we have eliminated it. It actually simplifies our study, now we don't have too many more control populations. And our purpose is really not to develop a biomarker for chronic fatigue syndrome. That's not what our goal is. We really want to study the pathophysiology and identify the immune abnormalities in these patients. So we decided to eliminate it anyhow. I think that's it.

Then we have healthy controls. And the post-Lyme — again, we've got a really nice cohort of patients here at NIH and so these individuals have had an infectious process and then recovered from it. So you have an infection and you get worse, you have an infection and you get better. So we were going to enroll only those patients that got better, so we're not looking at this chronic Lyme or post-Lyme and all that other kind of stuff. We really are looking at individuals that had a clear infectious process and actually got better. So in a way they are... they should look like, everything like a healthy control, is what I would expect them to be. So anyway, that's what we have for our study population.

OK, so this is my last slide. So I put down a few statements here because I think these were the kinds of questions that were... we've gotten from the communities. I thought I should try to address some of these things the best I can. And then I'm happy to elaborate on them further or take other questions.

So the first is, I think, since there's so much interest in our study, I thought it probably is good for you to get to know a little bit of my own expertise and what you might expect from me as the PI of this study. So as I mentioned earlier, you know, I started my career in neurovirology, initially studying rubella virus then HIV, when HIV came along.

And now more recently I've gotten involved in studying some of the endogenous retroviruses that we think are involved in neurological diseases. And then some of the new viruses that have come out, like Ebola is one of them that we have been studying in Liberia, and now recently Zika virus, so our lab is focused on these two viruses as well.

So that's... So I come from a virology background and I am an expert both in clinical neuroinfectious disease, neuroimmunology, and as well as the basic science. So I have a full-fledged laboratory that studies these things and I'm proud to say that there aren't that many people in the world who can really do both clinical medicine and basic science, especially in the neuroimmunology or infectious disease realm.

And so we have special expertise that is available and we are glad to try and apply it to this disease to see if we can find something for these patients. So.... But also I should also mention that I'm not looking to become the world's expert in ME/CFS. That's not my goal. I just want to use my expertise to try and see if I can find something in this population, and then let the extramural world take it and run with it, and all the experts that are out there could then pursue it further. So I have a very focused goal. I want to try and answer that, and then move on to all the other things that I do.

And, I guess, the second question is quite obvious. I've tried to address that several times as to why I'm focusing on just that one group. Because I think that's where I can make a difference, or at least lend my expertise.

The study design, yes. So, I think one of the misconceptions out there was that once you design your study, then that's it. And if you find any kind of flaw, that's the... the whole world is going to come tumbling down or something. That's not the case. Any study that we design is always a process and evolution. You never really.... You might think you've got a really good design but you never really know until you start enrolling patients. You find out that, oops, I wanted to do all these tests but actually the patients can't even undergo this. Or maybe we didn't think of this: we need to actually add something just because we found something in some patients when we started. Or we need another control group because… for whatever reason.

So there are a lot of things that will evolve and I expect that to happen here as well. So just because we have designed something doesn't mean that's the end-all. I think we will, over a period of time, continue to modify the study as we see necessary, moving along.

Advantages and disadvantages of doing studies in the intramural program.... So, as I said, the advantage is that we really have world-class expertise available, technology available, that other institutions do not have. And the disadvantage is that we cannot do very large studies. You know, we've received emails: “Oh, you should be doing 80”, “You should be doing 100-and-some patients”, or whatever. We can't do that. We have a small hospital and we have only very limited beds. And we have lots of diseases that we study over here. And so we don't have the ability to do very large studies. It doesn't make much sense to do them here. Once you get to that stage, you do them extramural.

Team-members of the study.... So there are a lot of people who are on our.... Full-time people are only going to be a nurse and a coordinator, but everybody else who's on this study is actually lending their time towards this study. They are doing it in addition to whatever else they've been doing, so those responsibilities haven't gone away but they are taking on additional responsibilities for this study. So in all, there are close to about 150 or so investigators who are giving variable amounts of time towards this study here. There's lots of people involved.

And.... But I think what has happened is because media were just so... and it started scrutinizing the few names I put up over there, that a lot of people now come to me and say that, “You know what, I don't want you mentioning my name,” and then the other people said, “I don't want to have anything to do with it, I've got enough things that I'm doing”. And so that's become a bit of a challenge for me especially when there are very prominent scientists that I've approached that never will say no, but then they become reluctant to answer emails and so on, so you're going to kind of start getting a feeling that people feel that, do they really want their name out there on these kind of things?

So, I think people have to be a little bit careful as to how critical you become. You can end up....We're here to try and help. You can end up antagonizing all these people and they are, you know, busy doing other things. They're all.... There's no reason for them.... You can't force people to study your disease. People have to do it because they think it's important to study. So you've got to think that we're on the same team. And we want to really try and help, but we can't do that if the very people you want to help become antagonistic towards you.

So the other thing is there are a lot of comments we've received about biases and stuff like that. So if you have a large team and you have hundreds of people studying this disease you can't just go and do a litmus test on everyone and say that, “OK, well, you have a bias. We're not going to let you study this disease”. If you've got to eliminate all kinds of people, you’re never going to be able to study anything. Rather, you do as you're designing your study whereby you don't have to worry about people's biases. I think that's the way to do these things.

If I, you know.... I‘ve made my career studying AIDS. If I said “OK, I'm going to do a litmus test on everybody who study AIDS in this country and if you have any kind of adverse views about gay people and this, that and the other, you know, you shouldn't be studying this”. And we'll never have made any kind of advances. I think we made lots of advances and we know that people have all kinds of biases and we shouldn't worry about those kind of things. What we really need to do is focus on the disease and on the patients and try to get to the bottom of the disease. And that's what my goal really is.

And then, communication with the community: I think that's important. So we're happy to communicate. And so our offices are also trying their best to communicate with people that they can. I personally answered emails for people as well. You also have to realize we are doing a lot of other daytime job, a lot of other things too, so we can't.... If you send me an email that's, you know, three pages long I'll not even have the time to read the thing. So they have to be short and I'll give out short answers. You know, I never learned to type so I’ve got to type with one finger here, and so there will be short answers but I try the best that I can in order to answer all of these things. You know, we don't have a 9-to-5 job here, it's a 24-hour job, even though we work for the government, and so we do the best we can and hopefully you will see that we've been responsive.

The other way that we try to communicate with the community is by putting up a webpage. A lot of the questions that we see are repetitious. They all seem very similar in many, many ways and so we thought the best thing to do is just to put up those questions there with appropriate answers and hopefully that is beneficial to everyone. And if there.... And then we modify it from time to time, depending on new questions that come up.