View the Post on the Blogby Cort Johnson

"Other patients suffer a severe, long lasting illness, for which treatment is ineffectual, and even after the parasite has finally been eliminated, some sequelae persist, affecting quality of life and continuing to cause the patient discomfort or pain" (LJ Robertson et al, 2010)

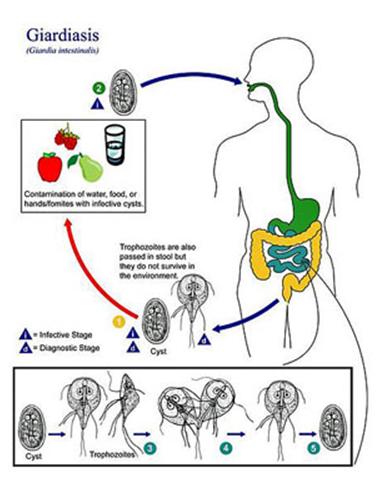

Giardia is an interesting bug. Perhaps the most common intestinal parasite in developing areas, it's not generally considered much of a threat in the developing world, but with a lowball figure of 20,000 cases the US in 2010 some researchers think of Giardia as a 're-emerging' infectious disease.

Giardia, though, is not normally considered a serious infection. Most people pass the bug quickly - and if they don't, effective antibiotic treatment is available; ie it's an 'uncomplicated infection' that the medical system believes it has largely taken care of and thus spends its energy on the big bugs like HIV.

Uncomplicated Infection?

An ongoing series of Norwegian ME/CFS studies suggest that the medical community should think again. They indicate that a Giardia infection, like many other pathogens that largely fly under the medical research system's radar, can be anything but uncomplicated. Let's take a look at what the three Norwegian Giardia studies found resulted from one outbreak in Bergen, Norway.

Anything But Uncomplicated

Their data suggests that Giardia infections can pose significant long term health risks. Three years after being exposed to a Giardia infection of their water supplies, almost 50% of those originally infected still had symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome and/or chronic fatigue.

Overall, being exposed to Giardia doubled their chances of experiencing significant fatigue, with five percent suffering from fatigue severe enough for them to lose employment or to be unable to continue their education.

All had taken anti-parasitic drugs and tests indicated that all had cleared the pathogen from their systems#.but three years later they were still ill.

What Had Happened?

Until more complete analyses are done it's hard to tell why and nobody knows#and unless more studies are done nobody will know. Several answers have been suggested#

Not Depression- The Norwegian studies indicated that depression and anxiety prior to becoming ill did not play a role.

- The Sneaky Pathogen theory - Low levels of the pathogen - as yet undetectable - are still present and producing a low grade inflammation that is causing fatigue, abdominal distress and other symptoms.

- The Hit and Run Theory - The pathogen damaged their intestinal surfaces causing permeability issues, hypersensitivity, bacterial overgrowth, immune reactions and irritable bowel syndrome.

The Other Immune System Problem - The Giardia attack triggered mast cell activation in the gut. Mast cell activation appears to be occurring in fibromyalgia and has been associated with fatigue, depression and psychological changes in irritable bowel syndrome.

CFS-Like Group - In the Bergen outbreak, questionnaires revealed - similar to ME/CFS - that the patients' physical functioning and vitality were hit the hardest. Higher rates of questionnaire-assessed anxiety and depression appeared to either be a feature of the illness itself and/or the result of having a chronic, poorly treated illness - not 'primary' depression.

Variable Appearance - While the infection was 'acute' (i.e. it happened suddenly), the time to distress varied dramatically. About 30% experienced debilitating fatigue immediately, but the months it took for approximately 60% of those infected to get really whacked with fatigue suggested that very different disease courses could occur in response to the same infection. Some studies do suggest that these allied disorders tend to merge together over time - that is, people with CFS tend to pick up IBS and IBS patients tend to meet the criteria for CFS as they 'mature into their illness'. (). Fatigue did not always occur at an early stage in the early myalgic encephalomyelitis outbreaks. It's possible that it simply took time for that symptom to 'flourish'.

Anyone who's gone backpacking and camping in the US and didn't filter their water could have been exposed to Giardia. I was exposed on a backpacking trip several years before I came down with chronic fatigue syndrome and later tests suggested it was still present. I also have IBS type symptoms - did Giardia contribute to my illness? I wouldn't be surprised at all, given all my abdominal complaints#

There are lots of options and, as we hear so often with ME/CFS, these authors believe that a number of little things go wrong in post-infectious giardia to create a big, bad thing:

"Thus, there is good reason to believe that predisposition for persistent giardiasis is based not on a single mechanism or defficiency, but rather on a combination of several minor de?ciencies of varying degrees in each individual's anti-Giardia defences."

Immune System

Tests revealed an activated immune system with increased numbers of cytotoxic (i.e. killer) T-cells on the prowl for invaders - a pattern also found in people with infectious mononucleosis, herpesvirus infections such as cytomegalovirus and herpes simplex, dengue fever, etc. That response, however, was more often found in people diagnosed with what the authors called post-giardiasis functional gastrointestinal disorders (people with IBS-like problems after a Giardia infection) than in people later diagnosed with ME/CFS. (Note that the Fukuda criteria was used to diagnose CFS#..).

Reduced NK cell functionality has been documented in ME/CFS, but studies of NK cell levels have had variable results. Several studies, including this one, found reduced NK cell levels in post-infectious patients, suggesting that both NK cell levels and functionality could be impaired in patients with infectious onset. This suggests that the NK cell level test could demarcate patients who got whacked with a bug (eg post-infectious patients) from those patients with other types of onset.

The Role of Infection (Any Infection?)

Infection is not just a trigger for chronic fatigue syndrome. Infections can also trigger fibromyalgia and irritable bowel syndrome. In fact, a recent meta-analysis indicated that having an acute attack of gastroenteritis - the stomach flu - results in a six-fold increase in one's risk of coming down with IBS a year later.

With a significant number of IBS patients also meeting the criteria for ME/CFS, it's clear that other infectious gastrointestinal pathogens trigger 'ME/CFS' as well and it's probably only a matter of time before they're added to the list. Ultimately people with severe fatigue and bad gut problems probably get diagnosed with ME/CFS or IBS depending on which doctors they see first.

Invisible Infections Wreaking Havoc?

Our medical system is good at hacking away at the big bugs - the HIVs, the Plasmodiums (malaria), the cholera and the West Nile Viruses - that leave obvious amounts of death and destruction in their wake, but it is very poor at examining the effects of bugs whose cost is not so immediate or obvious.

Enteroviruses are often also considered uncomplicated infections that sweep through a community, knock people out for a couple of days and then move on, but Dr Chia's findings suggest these infections can be life-changers for some. Long term follow-up studies of even common infectious events such as infectious mononucleosis, for instance, are rare outside of the CFS field.

ME/CFS researchers may be underfunded but they have been pioneering follow-up studies examining the insidious and long term effects that infections like Giardia, Epstein-Barr virus, SARS (sudden acute respiratory syndrome), parvovirus and coxsackie virus can have. As these studies get published - there have been two in the last year or so - hopefully the medical community will take a closer look at the mysterious effects that pathogens, some largely thought to be mere nuisances, can have - even after they've apparently been cleared from the body.

In the next year or so, major pathogen studies from the Chronic Fatigue Initiative (Lipkin and Hornig), the CFIDS Association of America, the CDC and probably the Whittemore Peterson Institute should be published. A Montoya study also appears to be under way and Dr. Mikovits recently reported that she and Dr. Ruscetti are continuing to look for bugs as well. The CFI study will be the most complete and rigorous and may, if reports are correct, finish up in the next couple of months.

Positive results in these studies would support the 'sneaky pathogen' theory; negative results would support the 'hit and run' theory. Probably we'll get a mixture of both...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Giardia Syndrome Strikes: Norwegian Studies Suggest Minor Bugs May Commonly Trigger CFS

- Thread starter Phoenix Rising Team

- Start date

So, from 2010 to now, any results?The CFI study will be the most complete and rigorous and may, if reports are correct, finish up in the next couple of months.

PubMed shows 83 search results for Robertson LJ. A quick review showed nothing of direct CFS merit since 2010 when the above article was published. There are two search results returned for CFS and Giardia. The article Treatment of Giardiasis gives a pretty good overview as well.

I find this type of study interesting, especially since I had untreated Giardia. But my symptoms went away in a few days time and it was about 20 years or so ago for me. It seems that if the Giardia idea were taken to be cuasitively related to CFS, there would be some distinct geographical clustering - perhaps a preponderance of CFS cases with backwoods Alaska, where I got mine.

Then, would need to add it to the growing and perhaps endless list of other things that could have been "hit and run" or in line with the "sneaky pathogen theory," as noted. Given it was hard to get a doctor to retest for Lyme and Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever - the former being negative at the time I contracted the latter - I cannot imagine the reaction I would get if I asked for a 20+ year old infection from Giardia. Will have to throw it around and see. For myself, I consider Giardia to be a doubtful but possible contender.

Thanks GG, it's because we had to post it to the blog twice as the first time it didn't post a forum thread, I've edited the link to point to the original blog article.

I believe PEM is likely caused by inflammation to various toxins and exhaustion of the anti-inflammatory neuropeptide system, as explained by Ritchie Shoemaker. I've read of credible people recovering from this symptom through mold avoidance. I also suspect some have recovered while receiving TPN for a relatively short while. I've postulated on another thread here that TPN might limit exposure to lipopolysaccharide long enough for neuropeptides to recover to the point that they keep inflammation at bay and interrupt the leaky gut cycle. So, yeah, I think the hit and run idea might have merit.