View the Post on the Blog

Bugs are not all bad, in fact many in our gut are essential to good health, but problems with these could help explain some diseases, possibly even ME/CFS. Simon McGrath takes an introductory look at the Microbiome - an area that is fast becoming a focus for several research teams looking at our own illness...

Home for gut microbes; few survive in the stomach but they flourish in the small intestine and dominate the colon - 60% of the dry weight of poop is bacteria.

Home for gut microbes; few survive in the stomach but they flourish in the small intestine and dominate the colon - 60% of the dry weight of poop is bacteria.

The microbiome - the bugs that live in our gut and on our skin - has become a hot topic, not least because of the coverage of 'faecal transplants' that apparently cure life-threatening infections by restoring the microbiome with poop from healthy donors.

There are some impressive stats around: with 100 trillion cells microbes outnumber our cells around 10:1 and there are around 5 million different gut microbe genes compared with around 25,000 human ones.

If it's any consolation, we are 98%+ human by weight - since the microbes are tiny - but it's probably more accurate to think of ourselves as mobile ecosystems rather than as pure human beings.

Peering into the microbiome

The microbiome refers to all the microbes in our gut and on our body: bacteria, fungi and single cell organisms (and even viruses). Technically, the microbiome refers to the collective genes of all the microbes (microbiome as in genome) while the microbes themselves are known as the microbiota, which is the term I'll use here.

The microbiota isn't just applicable to the gut but can apply all over our bodies: armpits, mouth, nose, skin and more. However, most research and this article will focus on the gut microbiota - the biggest and most important area.

We tend to think of microbes as nasty thing to be avoided, but the microbiota is surprisingly useful and probably essential to our survival, for reasons that include:

Thousands of different species can survive and thrive in the human microbiota, but most of us carry around 500 species. Our individual microbiotat normally remains stable over time, though each person's is distinct; even identical twins have different microbiota.

While there are many, many species of bacteria, in some way they play only a few different roles. The good guys are called 'symbionts', clearly paying their way e.g. those that make B vitamins and vitamin K.

The bad guys - the pathogens like cholera and amoebic dysentery - aren't really part of the microbiota at all. Neutral 'commensals' don't do anything directly good but don't harm us either, and may well help by simply crowding the unhelpful types, especially the 'pathobionts'. Actually, as well as 'crowding-out', some bacteria fight each other with lethal proteins.

'Pathobionts' include the infamous superbug Clostridium Difficile (C. diff for short) that usually sits there harmlessly in small numbers. However, in some situations - such as when helpful and neutral bacteria have been decimated by antibiotics, pathobionts show their Dark Side e.g. C. diff can take over causing bloody diarrhoea, which can be fatal in people already in poor health - and this is why C. diff can be so deadly in hospitals.

Microbiota and our immune systems

More immune cells are in the gut than anywhere else in the body, which makes sense as that's where most bugs are too. But it isn't simply bugs and our immune system facing off against each other: it turns out that the immune system needs the microbiota both to develop normally and to keep to keep it on an even keel. Germ-free mice, raised in sterile conditions, have no microbiota and are prone to some gut inflammatory diseases. This seems to be linked to problems with gut immune cells - particularly regulatory T cells (T-regs, shown in the photo), which we know don't develop properly in germ-free mice. T-regs help keep the immune system from over-reacting and setting off chronic inflammation; in particular they quieten down T-helper cells that otherwise rev up the immune system.

Out of balance

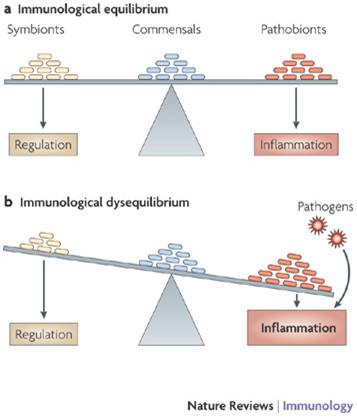

Dysbiosis is the fancy term for the gut bacteria getting out of balance, particularly the relationship with 'pathobionts', those bacteria that are harmless enough in small doses but can wreak havoc if given their head. The diagram opposite shows how an imbalance can lead to inflammation, which is what seems to be happening in Inflammatory Bowel Disease(IBD): for some reason there aren't enough of the symbionts that produce key molecules that help regulate the immune system, and inflammation results. There is also evidence in IBD that the body produces antibodies against helpful 'commensal' bacteria, and killing off the commensals would help the harmful pathobionts flourish.

Maybe, just maybe, microbiota problems are also behind the low levels of chronic inflammation and other immune dysfunction that is often seen in ME/CFS.

Cause or effect?

The central question in microbiota research is not are microbiota changes associated with diseases (they are in numerous cases)? But are the changes a cause of disease or simply a knock-on effect? The findings above for Inflammatory Bowel Disease suggest a causal role for microbiota, and the success of faecal transplant treatment for C. diff (see below) is the strongest evidence yet.

When these germ-free mice are given microbiota from lean mice they put on some weight, but they put on much more weight when given bacteria from obese mice. So perhaps one factor behind obesity is that some people have microbiota that help them extract more energy from food, and so put on more weight.

However, it is early days for such research and the relationship between disease and changes in microbiota remains uncertain.

Microbiota and ME/CFS

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in ME/CFS and could be linked to microbiota problems, and even chronic inflammation. Research on the microbiota is just beginning to appear in the ME/CFS literature:

Two important new microbiome studies underway

Invest in ME have raised £100,000 (wow) for a microbiome study aiming to establish 'whether microbe-driven inflammatory responses can provide an explanation for the pathophysiology of ME'. The study, run by the impressive Professors Tom Wileman at the University of East Anglia and Simon Carding at Norwich, began last October as a three-year studentship and initial results could emerge in 2015. They will be looking at the microbiota of ME patients including both bacteria and viruses, testing for leaky gut and using metabolomics to look at the metabolism of the whole microbiota.

Professor Ian Lipkin is focused on the microbiota for the same reason, particularly because his latest study found evidence of abnormal immune response in ME/CFS patients - could the microbiota be the cause? A microbiome study is underway: they plan to use a CFI cohort of 50 patients and 50 carefully-matched controls, but the study is held up by a lack of funds because the work they want to do is very expensive..

It may seem strange that bugs in our guts - not specific bugs, but an imbalance between different types - could cause ME/CFS, but that's just the line of research that Invest in ME and Lipkin are pursuing, focusing on a possible link with chronic inflammation. Microbiota in ME/CFS research is now taking off, and patients are helping make it happen.

BBC Gut Microbiota podcast (Weds 15 Nov; 28 minutes).

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research: @sjmnotes

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 (c)(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. and we'd love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help then please contact Mark through the Forum.

And don't forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online through the Phoenix Rising Store! To find out about more ways you can support Phoenix Rising, please visit our Donate page by clicking the button below.

View the Post on the Blog

Bugs are not all bad, in fact many in our gut are essential to good health, but problems with these could help explain some diseases, possibly even ME/CFS. Simon McGrath takes an introductory look at the Microbiome - an area that is fast becoming a focus for several research teams looking at our own illness...

The microbiome - the bugs that live in our gut and on our skin - has become a hot topic, not least because of the coverage of 'faecal transplants' that apparently cure life-threatening infections by restoring the microbiome with poop from healthy donors.

There are some impressive stats around: with 100 trillion cells microbes outnumber our cells around 10:1 and there are around 5 million different gut microbe genes compared with around 25,000 human ones.

If it's any consolation, we are 98%+ human by weight - since the microbes are tiny - but it's probably more accurate to think of ourselves as mobile ecosystems rather than as pure human beings.

But what's this all got to do with ME/CFS? Well, Ian Lipkin and others think microbiome problems could be behind the chronic inflammation that is often linked to our illness, and which may even be revealed as a cause of the disease.I think that the microbiome is going to be where the action is

Ian Lipkin

Peering into the microbiome

The microbiome refers to all the microbes in our gut and on our body: bacteria, fungi and single cell organisms (and even viruses). Technically, the microbiome refers to the collective genes of all the microbes (microbiome as in genome) while the microbes themselves are known as the microbiota, which is the term I'll use here.

The microbiota isn't just applicable to the gut but can apply all over our bodies: armpits, mouth, nose, skin and more. However, most research and this article will focus on the gut microbiota - the biggest and most important area.

We tend to think of microbes as nasty thing to be avoided, but the microbiota is surprisingly useful and probably essential to our survival, for reasons that include:

- making nutrients available, including making K and B vitamins

- helping protect us from disease by 'crowding out' harmful pathogens, much like a densely-planted garden border stops weeds from growing

- helping our immune system develop properly

The Good, the Bad, and the Somewhere in BetweenHow do we know?

The upsurge in microbiota research is driven by new tools to study it. The traditional way of identifying bacteria is to grow them in the lab until there are enough to study properly - but only 1% of gut microbes will grow in lab conditions, making the microbiota a black box til now. However, new sequencing technology means bacteria can be detected by their DNA (and RNA) and in minute quantities, without the need to grow it first. Ther are two main techniques:

- 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing: like us, bacteria have ribosome that make proteins, and the RNA of the ribosome is unique to each species - a handy fingerprint for identification.

- Full sequencing. A more difficult and expensive but more comprehensive approach is to sequence everything in the microbiome, to reveal every gene (5 million of them), giving a window on what the microbiota actually does and how it might interact with us. The full sequencing approach is also thought to give a more robust measure of the bacteria present and their relative quantities.

Thousands of different species can survive and thrive in the human microbiota, but most of us carry around 500 species. Our individual microbiotat normally remains stable over time, though each person's is distinct; even identical twins have different microbiota.

While there are many, many species of bacteria, in some way they play only a few different roles. The good guys are called 'symbionts', clearly paying their way e.g. those that make B vitamins and vitamin K.

The bad guys - the pathogens like cholera and amoebic dysentery - aren't really part of the microbiota at all. Neutral 'commensals' don't do anything directly good but don't harm us either, and may well help by simply crowding the unhelpful types, especially the 'pathobionts'. Actually, as well as 'crowding-out', some bacteria fight each other with lethal proteins.

'Pathobionts' include the infamous superbug Clostridium Difficile (C. diff for short) that usually sits there harmlessly in small numbers. However, in some situations - such as when helpful and neutral bacteria have been decimated by antibiotics, pathobionts show their Dark Side e.g. C. diff can take over causing bloody diarrhoea, which can be fatal in people already in poor health - and this is why C. diff can be so deadly in hospitals.

Microbiota and our immune systems

More immune cells are in the gut than anywhere else in the body, which makes sense as that's where most bugs are too. But it isn't simply bugs and our immune system facing off against each other: it turns out that the immune system needs the microbiota both to develop normally and to keep to keep it on an even keel. Germ-free mice, raised in sterile conditions, have no microbiota and are prone to some gut inflammatory diseases. This seems to be linked to problems with gut immune cells - particularly regulatory T cells (T-regs, shown in the photo), which we know don't develop properly in germ-free mice. T-regs help keep the immune system from over-reacting and setting off chronic inflammation; in particular they quieten down T-helper cells that otherwise rev up the immune system.

Out of balance

Dysbiosis is the fancy term for the gut bacteria getting out of balance, particularly the relationship with 'pathobionts', those bacteria that are harmless enough in small doses but can wreak havoc if given their head. The diagram opposite shows how an imbalance can lead to inflammation, which is what seems to be happening in Inflammatory Bowel Disease(IBD): for some reason there aren't enough of the symbionts that produce key molecules that help regulate the immune system, and inflammation results. There is also evidence in IBD that the body produces antibodies against helpful 'commensal' bacteria, and killing off the commensals would help the harmful pathobionts flourish.

Maybe, just maybe, microbiota problems are also behind the low levels of chronic inflammation and other immune dysfunction that is often seen in ME/CFS.

Cause or effect?

The central question in microbiota research is not are microbiota changes associated with diseases (they are in numerous cases)? But are the changes a cause of disease or simply a knock-on effect? The findings above for Inflammatory Bowel Disease suggest a causal role for microbiota, and the success of faecal transplant treatment for C. diff (see below) is the strongest evidence yet.

Faecal Transplants: Hard to swallow

The microbiota's big break in medicine was the faecal transplant to treat persistent infections - such a gross idea that the media could not resist covering it (or us resist reading it). Of course, gross is relative - patients suffering with intractable or even life-threatening C difficile infections often don't see it that way: "Because a fecal transplant is gross, but cramps and bloody diarrhea are aesthetically pleasing?", as one writer put it.

The microbiota's big break in medicine was the faecal transplant to treat persistent infections - such a gross idea that the media could not resist covering it (or us resist reading it). Of course, gross is relative - patients suffering with intractable or even life-threatening C difficile infections often don't see it that way: "Because a fecal transplant is gross, but cramps and bloody diarrhea are aesthetically pleasing?", as one writer put it.

Initially the reports of faecal transplant were simply anecdotal and I have to admit I thought it all sounded like woo science. Then came case studies and a systematic review of 317 cases found a 92% success rate. Finally a trial comparing faecal transplant against antibiotics for treating recurrent C. diff was stopped early because the faecal transplant was so much more effective than the antibiotic. Faecal transplants are entering the mainstream, but fortunately someone has just found a way to extract the bacteria from faeces and parcel them up in a simple pill: yum.

Initially the reports of faecal transplant were simply anecdotal and I have to admit I thought it all sounded like woo science. Then came case studies and a systematic review of 317 cases found a 92% success rate. Finally a trial comparing faecal transplant against antibiotics for treating recurrent C. diff was stopped early because the faecal transplant was so much more effective than the antibiotic. Faecal transplants are entering the mainstream, but fortunately someone has just found a way to extract the bacteria from faeces and parcel them up in a simple pill: yum.

And there are also examples of a causal relationship between microbiota and more complex illnesses. The best known case is obesity in mice. Germ-free mice, raised in sterile conditions, have no microbiota and tend to be thinner than normal laboratory mice. One possible reason for this is that the gut microbiota break down complex carbohydrates that mice can't digest on their own, making more food available.When these germ-free mice are given microbiota from lean mice they put on some weight, but they put on much more weight when given bacteria from obese mice. So perhaps one factor behind obesity is that some people have microbiota that help them extract more energy from food, and so put on more weight.

However, it is early days for such research and the relationship between disease and changes in microbiota remains uncertain.

Microbiota and ME/CFS

Gastrointestinal symptoms are common in ME/CFS and could be linked to microbiota problems, and even chronic inflammation. Research on the microbiota is just beginning to appear in the ME/CFS literature:

- Professor Kenny De Meirlier's small 2013 study on the microbiota of patients from Norway and Belgium had mixed results with differences seen between Norwegian patients but not between Belgian patients and controls.

- A recent paper details 60 CFS cases treated (in the 1990s) with colonic 'bacteriotherapy' and reported a 58% rate for "resolution of CFS symptoms", though it wasn't clear how the study measured outcomes.

- Pilot results from a CAA-funded microbiome study by Dr Shukla indicated that the microbiome of CFS patients responds differently to exercise than healthy controls. Data from the full study is now being analysed.

Two important new microbiome studies underway

Invest in ME have raised £100,000 (wow) for a microbiome study aiming to establish 'whether microbe-driven inflammatory responses can provide an explanation for the pathophysiology of ME'. The study, run by the impressive Professors Tom Wileman at the University of East Anglia and Simon Carding at Norwich, began last October as a three-year studentship and initial results could emerge in 2015. They will be looking at the microbiota of ME patients including both bacteria and viruses, testing for leaky gut and using metabolomics to look at the metabolism of the whole microbiota.

Professor Ian Lipkin is focused on the microbiota for the same reason, particularly because his latest study found evidence of abnormal immune response in ME/CFS patients - could the microbiota be the cause? A microbiome study is underway: they plan to use a CFI cohort of 50 patients and 50 carefully-matched controls, but the study is held up by a lack of funds because the work they want to do is very expensive..

If you want to make a donation of funds direct to this study, you can do so here. The team would also like to look at blood samples as well as the microbiome, but have yet to secure funding for this work. There will hopefully be a Phoenix Rising interview with Ian Lipkin about his microbiome project coming very soon, so do stay tuned.Ian Lipkin said:.. it is probably inappropriate for me to be passing the hat, but that’s precisely what I am doing.

It may seem strange that bugs in our guts - not specific bugs, but an imbalance between different types - could cause ME/CFS, but that's just the line of research that Invest in ME and Lipkin are pursuing, focusing on a possible link with chronic inflammation. Microbiota in ME/CFS research is now taking off, and patients are helping make it happen.

BBC Gut Microbiota podcast (Weds 15 Nov; 28 minutes).

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research: @sjmnotes

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 (c)(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. and we'd love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help then please contact Mark through the Forum.

And don't forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online through the Phoenix Rising Store! To find out about more ways you can support Phoenix Rising, please visit our Donate page by clicking the button below.

View the Post on the Blog

Last edited by a moderator: