Murph

:)

- Messages

- 1,799

https://hekint.org/2022/01/11/musical-evenings-on-hms-bounty/

THis is just a wonderful blogpsot on how they thought scurvy was psychological. Even Lind, the physician who ran history's first clinical trial and found the cure, continued to believe pscyhology mattered after he had the results in hand.

It's just a great illustration of how profound our belief in psychology can be, and shows how we interpret the positive attitude of the healthy as causal.

Missoula, Montana, United States

Dispatched to Tahiti in 1787 to gather breadfruit trees to be transplanted to the West Indies, HMS Bounty was a small ship with every possible inch allotted to botanical cargo. Spare too was the crew, which included no marines who might have acted as Lieutenant William Bligh’s bodyguards in the events to come. The crew did, however, include an Irish fiddler. In the tradition of the bard of King Alcinous’ court in The Odyssey, Michael Byrn was blind (or nearly so), which may explain why, amid the turmoil of the mutiny, he remained on the Bounty rather than scrambling into the launch that would carry Bligh and his party across the Pacific to safety in the Dutch East Indies. A lesser figure in the background of events, Byrn was tried for mutiny, maintained that he wished and intended to join Bligh when he (Bligh) was cast into the sea, and was acquitted. What was a fiddler doing on the Bounty in the first place?

The mutiny occurred just weeks before the storming of the Bastille and lives in the world’s imagination as an uprising against tyranny in its own right. Despite his reputation as a despot, however, Bligh valued high morale, and it seems he brought Byrn onto his ship with that in mind. Byrn’s fiddle would cheer the Bounty. And because the cheerful mind breathes health into the body, the fiddle would also help preserve the Bounty from disease—an urgent concern for any sea commander but perhaps especially for Bligh, who had served under a captain legendary for sailing to remote regions and back without losing a soul to scurvy: James Cook. If only because scurvy was at once deadly and yet (as Cook showed) preventable, Bligh felt that an outbreak at sea reflected disgrace on a ship and its commander. But prevention did not come easily. Keeping the Bounty scurvy-free meant instating not just a proper diet (even if its composition was still in question), but strict hygiene. The ship must be scrubbed down with vinegar, the men must keep themselves and their clothing clean, and—most significantly for our purposes—a good frame of mind must prevail. Reporting to his patron Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, on the mental hygiene of all those under him, Bligh wrote, “Both men & officers tractable and well disposed & cheerfulness and content in the countenance of every one. I am sure nothing is even more conducive to health.”1

Documenting Bligh’s preoccupation with hygiene, a recent investigator discusses compulsory dancing along with a diet evidently modeled on Cook’s.2 It was for the dance sessions that the fiddle was needed. Wrote Bligh in his log, “Some time for relaxation and mirth is absolutely necessary, and I have considered it so much so that after 4 o’clock, the evening is laid aside for their amusement and dancing. I had great difficulty before I left England to get a man to play the violin and I preferred at last to take one two-thirds blind than come without one.”3 Not that the men of the Bounty were free to enjoy themselves. Another private comment reveals the prescriptive nature of the Bounty’s evenings of mirth. “I have always directed the evenings from 5 to 8 o’clock to be spent in dancing, & that every man should be obliged to dance as I considered it conducive to their health.”4

In the light of events, one wonders how compliant the crew really was and how well the program of mandatory merriment went down with them. When the gunner’s mate and the assistant gardener, both of whom would join the mutiny, refused on one occasion to dance, Bligh “ordered their grog to be stopped with a promise of further punishment on a second refusal.”5 Others must have swallowed their resentment and performed their jigs. Ironically, the fiddler, aboard for the sole purpose of cheering one and all, seems to have been loved by none, while Bligh was tone-deaf to the irony of his musical edicts. The same failure of perception is at work in his scarcely credible portrait of the Bounty on the eve of the mutiny as “a ship in the most perfect order,” conveying a thousand plants likewise “in the most flourishing state,”6 as if the saplings were a living emblem of the vessel itself.

While Bligh misread the Bounty, his estimate of the importance of morale proved only too just in the end. During his party’s flight across the sea in an open boat following their severance from the Bounty, with his fellow refugees driven to the limits of their endurance if not beyond, “if any one of them had despaired, he would most probably have died before we reached New Holland [Australia]”: so Bligh reported in his narrative of the mutiny and its aftermath.7 In the event, through Bligh’s management of provisions, nursing of the sick, enforcement of discipline, and refusal to submit to demoralization, the boat reached Timor—a distance of some 3900 miles—without loss of life.

Even in ordinary nautical circumstances, however, Bligh believed morale could mean the difference between life and death. The curse of ships at sea was scurvy, its toll so dire that George Anson (later First Lord of the Admiralty) in the account of his voyage around the world in the 1740s tells of vessels that lost hundreds of men. Perhaps confusing the despair of the afflicted with a cause of the disease, a school of opinion that included Anson, held dejection itself to be a predisposing cause of scurvy. If the descent into scurvy begins with a loss of morale, then the commander who keeps his men in a state of good morale, at once disciplined and cheerful, might be said to hold the disease at bay. Bligh sought to do just that, imposing a regimen of gaiety in the hope of averting a plague all too familiar to every naval commander. As he wrote to his uncle from the Bounty, “Cheerfulness with exercise, and a sufficiency of rest are powerful preventatives to this dreadful disease [scurvy], a calamity which even at this present period destroys more men than is generally known. To assist in the first two particulars every opportunity I directed that the evenings should be spent in dancing.”8

Though Bligh’s insistence on hygiene, physical and moral, is easily caricatured as a neurotic obsession, the regimen he enforced was consistent with medical opinion at the time. Not even the best authorities on scurvy, including the man who wrote the book on it, James Lind, believed it could be reliably prevented or cured by diet alone. Though it was common nautical knowledge that fruits like oranges and lemons fend off scurvy—hence Lind’s use of them in the 1747 experiment aboard HMS Salisbury now celebrated as the first controlled clinical trial—Lind never attributed scurvy to any single factor. Not only deficient diet but moist, cold air and damp quarters, among other influences, tend to produce the disease. Consistent with this environmental perspective is Lind’s considered judgment, expressed at the end of the third and last edition of his weighty Treatise on the Scurvy (1772), that scurvy is bred by confinement. Dwelling below decks means being trapped in bad air, stifled, unable to expel digestive wastes through the skin. Dejection or melancholy, for its part, might be likened to stifling in the bad air of one’s own thoughts.

Those who imagine that Lind’s Treatise concerns oranges and lemons will be surprised to discover that his now-famous trial went nowhere and that at many points he implicates mood and frame of mind in scurvy. Thus, in a discussion of the causes of the disease he observes, “The passions of the mind are found to have a great effect. Those that are of a cheerful and contented disposition, are less liable to it [that is, scurvy], than others of a discontented and melancholy turn of mind.” (In this context, Bligh’s private comments on the docility and good disposition of the Bounty’s crew—observations that seem hopelessly inapt in the light of the mutiny—read like the notes of one watchful for warning signs of disease and relieved by their seeming absence.) While a dietary deficiency may be the immediate (in Lind’s terms, the “occasional”) cause of scurvy, bad diet alone might not be enough to produce scurvy in a constitution untouched by such predisposing causes as confinement, inactivity, and despair, just as a debilitated constitution can lead to scurvy even in the presence of good diet. According to Lind, scurvy is an inexplicable disease with no single cause or treatment, and all contributing causes, including the darker “passions of the mind,” have the effect of weakening digestion and obstructing perspiration, which are scurvy’s mechanisms.9 It appears Bligh had an edition of Lind’s Treatise with him on the Bounty.10

For the prevention of scurvy, Lind advises removal into dry surroundings, fresh fruits and vegetables, and “contentment of mind, procured by agreeable and entertaining amusements.”11 Bligh did his utmost to keep the Bounty dry, obtained fresh food when possible, and enacted Lind’s recommendation of amusement in a sort of direct and literal manner. Along with a good diet per se, the crew should be fed a good diet of entertainment.

continues at link: https://hekint.org/2022/01/11/musical-evenings-on-hms-bounty/

THis is just a wonderful blogpsot on how they thought scurvy was psychological. Even Lind, the physician who ran history's first clinical trial and found the cure, continued to believe pscyhology mattered after he had the results in hand.

It's just a great illustration of how profound our belief in psychology can be, and shows how we interpret the positive attitude of the healthy as causal.

Musical evenings on HMS Bounty

Stewart JustmanMissoula, Montana, United States

|

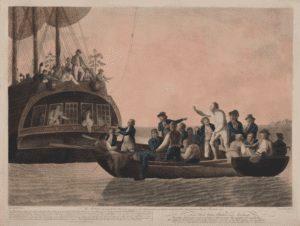

| The mutineers turning Bligh and his crew from the Bounty, 29th April 1789. Illustration by Robert Dodd. 1790. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. |

The mutiny occurred just weeks before the storming of the Bastille and lives in the world’s imagination as an uprising against tyranny in its own right. Despite his reputation as a despot, however, Bligh valued high morale, and it seems he brought Byrn onto his ship with that in mind. Byrn’s fiddle would cheer the Bounty. And because the cheerful mind breathes health into the body, the fiddle would also help preserve the Bounty from disease—an urgent concern for any sea commander but perhaps especially for Bligh, who had served under a captain legendary for sailing to remote regions and back without losing a soul to scurvy: James Cook. If only because scurvy was at once deadly and yet (as Cook showed) preventable, Bligh felt that an outbreak at sea reflected disgrace on a ship and its commander. But prevention did not come easily. Keeping the Bounty scurvy-free meant instating not just a proper diet (even if its composition was still in question), but strict hygiene. The ship must be scrubbed down with vinegar, the men must keep themselves and their clothing clean, and—most significantly for our purposes—a good frame of mind must prevail. Reporting to his patron Joseph Banks, President of the Royal Society, on the mental hygiene of all those under him, Bligh wrote, “Both men & officers tractable and well disposed & cheerfulness and content in the countenance of every one. I am sure nothing is even more conducive to health.”1

Documenting Bligh’s preoccupation with hygiene, a recent investigator discusses compulsory dancing along with a diet evidently modeled on Cook’s.2 It was for the dance sessions that the fiddle was needed. Wrote Bligh in his log, “Some time for relaxation and mirth is absolutely necessary, and I have considered it so much so that after 4 o’clock, the evening is laid aside for their amusement and dancing. I had great difficulty before I left England to get a man to play the violin and I preferred at last to take one two-thirds blind than come without one.”3 Not that the men of the Bounty were free to enjoy themselves. Another private comment reveals the prescriptive nature of the Bounty’s evenings of mirth. “I have always directed the evenings from 5 to 8 o’clock to be spent in dancing, & that every man should be obliged to dance as I considered it conducive to their health.”4

In the light of events, one wonders how compliant the crew really was and how well the program of mandatory merriment went down with them. When the gunner’s mate and the assistant gardener, both of whom would join the mutiny, refused on one occasion to dance, Bligh “ordered their grog to be stopped with a promise of further punishment on a second refusal.”5 Others must have swallowed their resentment and performed their jigs. Ironically, the fiddler, aboard for the sole purpose of cheering one and all, seems to have been loved by none, while Bligh was tone-deaf to the irony of his musical edicts. The same failure of perception is at work in his scarcely credible portrait of the Bounty on the eve of the mutiny as “a ship in the most perfect order,” conveying a thousand plants likewise “in the most flourishing state,”6 as if the saplings were a living emblem of the vessel itself.

While Bligh misread the Bounty, his estimate of the importance of morale proved only too just in the end. During his party’s flight across the sea in an open boat following their severance from the Bounty, with his fellow refugees driven to the limits of their endurance if not beyond, “if any one of them had despaired, he would most probably have died before we reached New Holland [Australia]”: so Bligh reported in his narrative of the mutiny and its aftermath.7 In the event, through Bligh’s management of provisions, nursing of the sick, enforcement of discipline, and refusal to submit to demoralization, the boat reached Timor—a distance of some 3900 miles—without loss of life.

Even in ordinary nautical circumstances, however, Bligh believed morale could mean the difference between life and death. The curse of ships at sea was scurvy, its toll so dire that George Anson (later First Lord of the Admiralty) in the account of his voyage around the world in the 1740s tells of vessels that lost hundreds of men. Perhaps confusing the despair of the afflicted with a cause of the disease, a school of opinion that included Anson, held dejection itself to be a predisposing cause of scurvy. If the descent into scurvy begins with a loss of morale, then the commander who keeps his men in a state of good morale, at once disciplined and cheerful, might be said to hold the disease at bay. Bligh sought to do just that, imposing a regimen of gaiety in the hope of averting a plague all too familiar to every naval commander. As he wrote to his uncle from the Bounty, “Cheerfulness with exercise, and a sufficiency of rest are powerful preventatives to this dreadful disease [scurvy], a calamity which even at this present period destroys more men than is generally known. To assist in the first two particulars every opportunity I directed that the evenings should be spent in dancing.”8

Though Bligh’s insistence on hygiene, physical and moral, is easily caricatured as a neurotic obsession, the regimen he enforced was consistent with medical opinion at the time. Not even the best authorities on scurvy, including the man who wrote the book on it, James Lind, believed it could be reliably prevented or cured by diet alone. Though it was common nautical knowledge that fruits like oranges and lemons fend off scurvy—hence Lind’s use of them in the 1747 experiment aboard HMS Salisbury now celebrated as the first controlled clinical trial—Lind never attributed scurvy to any single factor. Not only deficient diet but moist, cold air and damp quarters, among other influences, tend to produce the disease. Consistent with this environmental perspective is Lind’s considered judgment, expressed at the end of the third and last edition of his weighty Treatise on the Scurvy (1772), that scurvy is bred by confinement. Dwelling below decks means being trapped in bad air, stifled, unable to expel digestive wastes through the skin. Dejection or melancholy, for its part, might be likened to stifling in the bad air of one’s own thoughts.

Those who imagine that Lind’s Treatise concerns oranges and lemons will be surprised to discover that his now-famous trial went nowhere and that at many points he implicates mood and frame of mind in scurvy. Thus, in a discussion of the causes of the disease he observes, “The passions of the mind are found to have a great effect. Those that are of a cheerful and contented disposition, are less liable to it [that is, scurvy], than others of a discontented and melancholy turn of mind.” (In this context, Bligh’s private comments on the docility and good disposition of the Bounty’s crew—observations that seem hopelessly inapt in the light of the mutiny—read like the notes of one watchful for warning signs of disease and relieved by their seeming absence.) While a dietary deficiency may be the immediate (in Lind’s terms, the “occasional”) cause of scurvy, bad diet alone might not be enough to produce scurvy in a constitution untouched by such predisposing causes as confinement, inactivity, and despair, just as a debilitated constitution can lead to scurvy even in the presence of good diet. According to Lind, scurvy is an inexplicable disease with no single cause or treatment, and all contributing causes, including the darker “passions of the mind,” have the effect of weakening digestion and obstructing perspiration, which are scurvy’s mechanisms.9 It appears Bligh had an edition of Lind’s Treatise with him on the Bounty.10

For the prevention of scurvy, Lind advises removal into dry surroundings, fresh fruits and vegetables, and “contentment of mind, procured by agreeable and entertaining amusements.”11 Bligh did his utmost to keep the Bounty dry, obtained fresh food when possible, and enacted Lind’s recommendation of amusement in a sort of direct and literal manner. Along with a good diet per se, the crew should be fed a good diet of entertainment.

continues at link: https://hekint.org/2022/01/11/musical-evenings-on-hms-bounty/