Normally we comment on recent research but there were a series of papers from Simon Wessely and colleagues that are still cited and have become quite influential, so I thought they should have their own thread. Some have already been discussed in part on other threads. The papers seem to come out of a single large study done in the early 1990s:

Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress, 1994

T. Pawlikowska, T. Chalder, S. R. Hirsch, P. Wallace, D. J. Wright, and S. C. Wessely

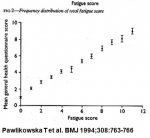

The ultimate source of the normative fatigue data used in the PACE trial, and source of the graph linking psychological morbidity to fatigue

Postinfectious fatigue: prospective cohort study in primary care, 1995 (pdf), 1995, Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, Pawlikowska T, Wallace P, Wright DJ.

Basis for claim there is no link between common viral infectons and CFS

Psychological symptoms, somatic symptoms, and psychiatric disorder in chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective study in the primary care setting, 1996 (pdf). S Wessely, T Chalder, S Hirsch, P Wallace and D Wright

Source of a graph linking number of CDC symptoms to psychological morbidity.

The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. 1997. S Wessely, T Chalder, S Hirsch, P Wallace and D Wright

Claims a prevalence of 2.6% for CFS (CDC 94 criteria) in the UK.

Population based study of fatigue and psychological distress, 1994

T. Pawlikowska, T. Chalder, S. R. Hirsch, P. Wallace, D. J. Wright, and S. C. Wessely

The ultimate source of the normative fatigue data used in the PACE trial, and source of the graph linking psychological morbidity to fatigue

Postinfectious fatigue: prospective cohort study in primary care, 1995 (pdf), 1995, Wessely S, Chalder T, Hirsch S, Pawlikowska T, Wallace P, Wright DJ.

Basis for claim there is no link between common viral infectons and CFS

Psychological symptoms, somatic symptoms, and psychiatric disorder in chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective study in the primary care setting, 1996 (pdf). S Wessely, T Chalder, S Hirsch, P Wallace and D Wright

Source of a graph linking number of CDC symptoms to psychological morbidity.

The prevalence and morbidity of chronic fatigue and chronic fatigue syndrome: a prospective primary care study. 1997. S Wessely, T Chalder, S Hirsch, P Wallace and D Wright

Claims a prevalence of 2.6% for CFS (CDC 94 criteria) in the UK.