View the Post on the Blog

View the Post on the Blog

The CDC PCOCA telephone broadcast on 10 September 2013, featured a lengthy presentation from Dr Ian Lipkin who revealed some stunning initial results from the study that is primarily hunting for pathogens in ME/CFS. Simon McGrath and Russell Fleming (Firestormm) review this exciting and possibly game-changing news...

Dr Ian Lipkin

Lead Researcher

Chronic Fatigue Initiative (CFI)

Pathogen Discovery and Pathogenesis Study

Read the full Lipkin Transcript: Here.

Dr Ian Lipkin has been a human whirlwind in ME/CFS research since he became involved a few years back, and he's just surprised us all by announcing the first results from the world's largest ever biomedical ME/CFS study in a public broadcast!

He started off by lowering expectations: their results thus far do not implicate a single infectious agent and they have not discovered the cause of CFS. But he then wowed the hundreds listening to the conference call by revealing they had found strong evidence for immune overstimulation, both in blood plasma and in cerebro spinal fluid; and that they were now hard at work trying to identify what could be causing these abnormalities.

The big pathogen hunt draws a blank thus far

This study is looking exhaustively for any pathogen: viral, bacterial, fungal or parasitic, to see if a chronic infection could explain ME/CFS. Many of the results are in, but so far there is no clear sign of viruses at least. It is every bit a collaborative effort, with patients provided by long-established physicians including Dr Dan Peterson and Professor Jose Montoya.

The Key Players

Lipkin began by thanking the clinicians who had provided the all-important samples. Effectively it was a roll call of America's top ME/CFS physicians:

Professors Jose Montoya, Anthony Komaroff and Nancy Klimas; and Drs Dan Peterson, Lucinda Bateman, Sue Levine and Donna Felsenstein.

The study itself was run by Dr Mady Hornig (CFI Principal Investigator) at the Centre for Infection and Immunity at Mailman School of Public Health; where Lipkin is also based.

He went on to acknowledged the very necessary support of the Chronic Fatigue Initiative, the Evans Foundation and an anonymous donor supporting Montoya's work.

First the researchers looked at blood plasma for 285 CFS patients and 201 controls from Jose Montoya at Stanford (these are serious numbers). They searched for genetic evidence of infection using a panel that was able to detect 20 specific bacteria, viruses or parasites; including Epstein-Barr virus, Human Herpes Virus 6, enteroviruses, Influenza A and Borrelia bacteria.

Next they used high throughput sequencing, a method that was pioneered by Lipkin and colleagues that was used to discover over 500 viruses – so they felt fairly confident that if a virus was present, then they would have found it.

But they effectively drew a blank using both methods - only 1.4% of CFS patients were found to have HHV6 infection, but so did 1% of controls.

Other findings...

Lipkin said they also found Anelloviruses in 75% of those studied in plasma samples, but it was not specific for Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (we don't currently have separate figures for patients and controls). Anellovirus is believed to cause widespread chronic infection in the human population, but has not yet been associated to any specific disease. "I really don’t know at this point what this finding means" said Lipkin.

They also found retroviruses in 85% of the sample pools. However, Lipkin expressed caution:

"It is very difficult at this point to know whether or not this is clinically significant. And given the previous experience with retroviruses in Chronic Fatigue, I am going to be very clear in telling you – although I am reporting this at present – in Professor Montoya’s samples neither he nor we have concluded that there is a relationship to disease ...if I were to place bets and speculate, I would say that this is not going to pan out."

Window on the brain: Cerebrospinal fluid samples

Both Lipkin and Hornig were clearly excited to have had access to the 60 cerebrospinal fluid samples from Peterson, and kindly donated by his ME/CFS patients. Cerebrospinal fluid bathes our brain and spinal cord so it gives access to what goes on in the brain, a prime site of interest to researchers, but hard to access; so these spinal tap samples are precious.

However, using the same molecular techniques to track down pathogens as they had applied to Jose Montoya's samples, Lipkin's team again drew a blank.

At the Invest in ME conference in May, Hornig said they had tentative findings that there might just be a novel pathogen or pathogen candidate in these samples - but it was too early to say for sure. In reply to a question yesterday, Lipkin said there is no more to report:

Nonetheless, he also said they hadn't finished all the DNA sequencing work on these samples, so this is not yet a dead end.

"we do not yet have a novel pathogen nor do we have a pathogen candidate in which I would have any confidence. So at this point we have no plans to publish anything."

Immune stimulation and biomarkers

Up to this point we'd heard a lot of very impressive negative findings, based on large, well-defined samples of patients and controls, and using powerful research techniques. But what we most wanted to hear about was positive leads - and Ian Lipkin duly obliged:

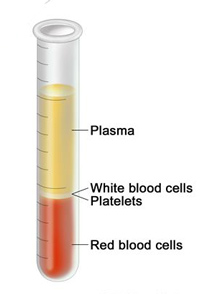

Plasma is the clear fluid left when blood is separated

They took plasma from the CFI cohort of 200 very well-defined ME/CFS cases and 200 controls collected by clinicians (See 'Key Players' above). Then they searched for cytokines and chemokines, which are regulators and controllers of the immune system.

The big finding was a decrease in levels of Interleukin's IL-17, IL-2, IL-8 and in TNF-alpha - all of which have a role in pro-inflammatory responses. Lipkin believes these significant differences are worth follow-up in larger cohorts to better understand what they mean.

Professor Jonathan Edwards (who is an adviser to the planned UK Rituximab trial) commented on this forum yesterday, that it was a surprise to see TNF-alpha levels decrease, and suggested it could mean that 'inflammation' is too crude a concept for the process.

Lipkin and colleagues also found upregulation in Leptin, a hormone that plays a key role in regulating energy uptake and use, and Serpin, a protein family with multiple roles. More obscure cytokines, and and their cousins chemokines, were also affected but Lipkin didn't give any further detail.

Two new patient types revealed

Ian Lipkin said they found something very surprising in their data: there appear to be substantial differences in profiles between those people who have had the disease for 3 years or less and those who have had the disease for more than 3 years. And that this is important because, "it could have implications for therapy as well as for diagnosis".

In the ‘early group’, who have been ill for less than 3 years, there seem to be a number of markers suggestive of some sort of allergy aspect. For example there are often increased numbers of eosinophils in blood, with more differences in cytokines. But while this is tentative, he was more confident in the finding the IL-17 was elevated in these 'early' patients, compared with reduced levels in patients ill for over three years.

Lipkin said that he thought this 3-year division could be very important and that it hadn't been something they were looking for; but would be looked at in any future work they did.

Cerebrospinal fluid: different differences

Lipkin's team also found differences in cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers between patients and controls. I'm not sure from what he said if there were significant differences between the 'early' group and patients who had been ill for more than three years. However, they did find that patients had elevated levels of the TH-2 type cytokines IL-10 and IL-13 and elevated levels of four TH-1 cytokine: IL-1 beta, TNF-alpha, IL-5, and IL-17. Lipkin said this is compatible with a profile of some particular types of response that may provide insights into immunological dysregulation in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.

So, overall they found clear differences between patients and controls in both plasma and spinal fluid. Many immune differences have been detected before, but findings are not very consistent and none had used such a large and robustly-defined patient cohort (meeting Fukuda and Canadian criteria), or with such carefully matched controls.

HEALTH WARNING

Dr Ian Lipkin again was very clear that he did NOT recommend anyone act on these provisional findings: he doesn't want anyone to get a spinal tap, or measure the cytokine levels and hope to modulate them with drugs based on this research: it's too early for that.

The lost years...

Back in 1999 Ian Lipkin published his first paper on CFS, which ruled out a connection between the illness and Borna Disease Virus (one of the many viruses he's discovered). But crucially they found evidence of polyclonal B-cell reactivity. He commented that back then:

"there was a very strong sentiment in some portions of the scientific and clinical communities – not always and not everywhere – but in some portions of the community, that this was a psychological illness. What I said was that based on our findings we had very strong evidence that people with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome were truly ill with a physical illness and they deserved a "Deep Dive" to find out why they were ill." He noted that was a long time ago and dryly added "I am pleased to see that people are now paying much more attention to this disorder and what we can do about it".

What next?

"I still believe the primary cause is likely to be an infectious agent."Having found clear signs of cytokine abnormalities, Lipkin wants to find out what is causing these changes; he currently thinks that an ongoing stimulus is causing immune system activation which might be resulting in the symptoms we associate with the disease. And interestingly, he still believes that infection lies at the root of it all - despite not yet finding any infections.

The team - working closely with the clinicians he's already mentioned - plan even more extensive work on a cohort of 200 CFI patients and controls. They will further test for viruses and crucially they will also look for bacteria and fungi by sequencing ribosomal RNA (which should detect unknown bacteria and fungi, as well as known ones).

Previous infection detection

The group has looked for current pathogens in the blood and spinal fluid samples they have - and has so far drawn a blank, though there is more work underway. However, what if the trigger for ME/CFS is an earlier infection that has since been cleared: the 'hit and run' scenario Hornig has described? Lipkin says they are looking for "shadows" of previous infections by searching for antibodies against specific infections, rather than the infections themselves (the body will continue to produce low levels of specific antibodies years after an infection has been cleared (the basis of much immunity)).

They will use a technique called LIPS to look for antibodies against particular known infection. In addition, as in their viral sequencing work, they will use an 'unbiased' system (using peptide arrays) that should detect all potential viruses - or rather antibodies against them. They don't currently have an 'unbiased' system that works on bacteria or fungi.

Fecal future?

What excites Ian Lipkin most is the gut microbiome, the community of micro-organisms that live in our gut - which might seem odd given his focus so far on pathogens and the immune system. However, it turns out that the microbiome can have a profound influence on the immune system and may be important in many diseases. Hornig and Lipkin have already developed techniques to study the microbiome, and have shown it could be a factor in autism and even in the severity of colon cancer.

It turns out the best way to find out what lives in the microbiome is to measure what comes out of the gut: fecal matter, or 'poop' to you and me. Their ME/CFS microbiome project has started, but Lipkin felt there wasn't enough material in the first attempt at gathering samples, so things have been delayed as they switch to a new technique (the 'special' collection cups).

The Big Ask: "we can't do this without you"

Microbiome research is very expensive (analysis, not sample collection), and they currently only have the funds to do 10% of what's needed. In fact, throughout the call, Lipkin was stressing the need for more funds, because good research costs and ME/CFS is woefully underfunded: there just isn't enough money to do the work needed. The current science budget cuts (Sequestration) in the US makes the climate even harder.

"It is probably inappropriate for me to be passing the hat, but that’s precisely what I am doing."

He urged patients to contact their representatives in Congress, demanding more funding for ME/CFS research - pointing out that in the early days of HIV, there was little funding until patients demanded it. He also said that if patients were able to afford it, they should invest in research themselves.

Conclusion

ME/CFS research is coming of age. Ian Lipkin has reported these early - and soon-to-be published results - from a huge study, using 285 of Jose Montoya's patients, the 200 patients from the Chronic Fatigue Initiative, plus the 60 'gold-dust' spinal fluid samples from Dan Peterson's patients. Using state-of-the-art techniques, they have largely ruled out a role for a specific pathogen - though that work is incomplete. And they have strong evidence of ongoing immune stimulation in ME/CFS patients, with abnormalities found in both the blood and spinal fluid. The next stage involves deeper searching for bacteria and fungi, looking for 'shadows' of previous infections and investigating the gut microbiome. These are exciting times!

Thanks to the CDC for organizing the presentation and to Firestormm for providing a transcript of this talk, and above all to Dr Ian Lipkin for taking time out to talk to patients.

If you would like to donate to Ian Lipkin's research, click here. In the comments box, put "for M.E/C.F.S Study" to make sure it goes to the right place.

Simon McGrath tweets on ME/CFS research:

Phoenix Rising is a registered 501 c.(3) non profit. We support ME/CFS and NEID patients through rigorous reporting, reliable information, effective advocacy and the provision of online services which empower patients and help them to cope with their isolation.

There are many ways you can help Phoenix Rising to continue its work. If you feel able to offer your time and talent, we could really use some more authors, proof-readers, fundraisers, technicians etc. and we'd love to expand our Board of Directors. So, if you think you can help then please contact Mark through the Forum.

And don't forget: you can always support our efforts at no cost to yourself as you shop online! To find out more, visit Phoenix Rising’s Donate page by clicking the button below.

View the Post on the Blog

Last edited by a moderator: